What are anthocyanins?

Anthocyanins are a family of pigments found in many plants that confer red/purple/blue coloration. While there are many kinds of anthocyanin pigments, they all share the same core structure consisting of a flavylium backbone (highlighted in Fig. 1 below) [13]. This backbone is then modified to give a variety of pigments with different properties. Anthocyanins are produced in a well-characterized biochemical pathway which uses phenylalanine (an amino acid, such as you might find in protein powder) as the starting point [13][23].

Figure 1: Nasunin, an anthocyanin found in eggplants. Image taken from the Pubchem compound summary for Nasunin [17]. The green square highlights the location of the modified flavylium backbone.

Where can I see anthocyanins?

Plants with observable anthocyanins are all over the place! If a plant is a rich red to purple color, there is a reasonable chance that this coloration is due to anthocyanin pigments (though it is always a good idea to do an online search to be sure). One common example of a plant with clearly visible anthocyanin pigments is the japanese maple (Acer palmatum), which often possesses leaves with red or darker coloration. It’s a popular garden plant; I’m sure you could find one if you look!

Anthocyanins are also present in plants eaten for food. Particularly striking examples include red cabbage, red grapes, and many kinds of darkly-colored berries, but there are many others.

Figure 2: Many eggplants are a dark purple color due to the presence of anthocyanin pigments.

What do anthocyanins do?

One popular theory is that anthocyanins give plants protection from high light levels. Of course, plants need light for photosynthesis, but once a certain rate of photosynthesis has already been achieved, excess light increases the chance that valuable photosynthetic machinery could be damaged (since light can drive chemical reactions!). Anthocyanins absorb excess light, thus preventing damage to the photosynthetic machinery.

Demonstrating the protective effect of anthocyanins is not trivial from a scientific perspective. To do this, you would need to compare some aspect of photosynthetic performance in two groups of plants subjected to high light levels. These two groups of plants should be as similar as possible to each other in every way (minimize the number of variables!), and should ideally differ only in anthocyanin content. Hypothesis: If anthocyanins protect photosynthetic machinery from damage, then we would expect “improved” photosynthetic performance in the group of plants with high anthocyanin content, as compared to the plants with lower anthocyanin content.

I have added a link here to a study by Gould et al. (2018) which does exactly this [5]! In this study, they use a plant called Arabidopsis thaliana, which is commonly used in scientific research (think lab rat, but green and leafy). Their Arabidopsis strain with relatively low anthocyanin content is called Col-0 (Columbia-0). Col-0 is a so-called “wild-type” strain, meaning that it is a direct descendent of an Arabidopsis ancestor collected in the field, which has not been genetically modified. Their Arabidopsis strain with high levels of anthocyanins is called pap1-D, which is a descendent of Col-0 (hence, very similar!). However, pap1-D has been genetically modified to overexpress the PAP1 gene, which in turn causes over-accumulation of anthocyanins. (More information about pap1-D may be found here: [2]).

To assess photosynthetic performance, they measured the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm). The precise definition of this term is beyond the scope of this blog post, but more information can be found in this excellent article here: [15]. Generally speaking, a high Fv/Fm value indicates efficient photosynthesis, while a lower Fv/Fm indicates inefficient photosynthesis (possibly due to light-induced damage). Gould et al. measured Fv/Fm before and after exposing plants to high light levels, and noted the decrease in Fv/Fm following high light exposure. The pap1-D plants, which contain higher levels of anthocyanins, showed a smaller reduction of Fv/Fm following high light exposure than the Col-0 plants (indicating less accumulated damage). This result agrees with our hypothesis!

Given that anthocyanins indeed appear to protect plants against high light levels, it makes sense that anthocyanin production can itself be regulated by the prevailing light conditions. In Arabidopsis, blue light and UV-B in particular promote anthocyanin accumulation, more so than other colors of light [1][6][8].

What else do anthocyanins do?

Anthocyanins are also produced in response to other kinds of stress, such as drought stress [11]. Indeed, this interesting paper [16] by Nakabayashi and colleagues shows that our old friend, pap1-D, has improved survival in controlled drought conditions as compared to Col-0. Exactly why this occurs is unclear, but the antioxidant properties of anthocyanins may help to relieve oxidative stress induced by drought conditions, and water loss from pap1-D plants in drought conditions may be marginally lower than in Col-0 [16].

Anthocyanin content is also a desirable trait that is often selected for in domesticated plants. Why? Because it looks cool. And there’s no better reason than that.

There is some interest in the nutritional value of anthocyanins, and many claims of health benefits, particularly owing to their antioxidant properties [7]. For now, I would consider these claims with considerable caution. Benefits to human health are difficult to assess, because experimenting on people is often unethical, and the results of epidemiological studies can be difficult to interpret. One study using rats as a model to study myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) did find that infarction size (volume of dead tissue within hearts whose blood supply had been artificially restricted) was modestly reduced in rats who had been fed a diet high in maize anthocyanins for 8 weeks vs. those fed a diet lacking anthocyanins [25]. (If you are a bit lost like I was while reading this article, there’s good background information here: [4]). Another study in rats claimed to find evidence that anthocyanins in soybean are protective against obesity [9]. It is unclear whether these effects translate to humans at all, so more work is needed before we can confidently discuss the roles that anthocyanins play in human health.

Anthocyanins in tomatoes:

We will (hopefully!) talk a fair bit about sunflowers and tomatoes in this blog. This is because:

- They are super easy to grow if you have the time and space!

- There are many varieties of each, which have been selectively bred to exhibit various desirable traits.

Comparing different cultivars of sunflower and tomato gives us a great stepping-in-point to discuss many concepts in plant science.

Now, we have a few different varieties of tomato growing on our deck. I don’t really like tomatoes. I suppose they’re nice in caprese salad. Whatever. They’re still fun to grow.

I’ve been observing the development of two particular varieties with great interest. One variety, “Indigo Blue Beauty,” exhibits purple coloration on stems and developing fruits, which is due to the presence of anthocyanins (Fig. 3). Compare this to another variety, “Black Krim,” which has does not have observable anthocyanin accumulation in either part. Actually, Black Krim is a variety known for darker-colored fruits… but in this case, a different pigment called pheophytin – not an anthocyanin – is responsible [21].

Figure 3: Left: Stem and developing fruit of tomato “Indigo Blue Beauty.” Right: Stem and developing fruit of tomato “Black Krim.”

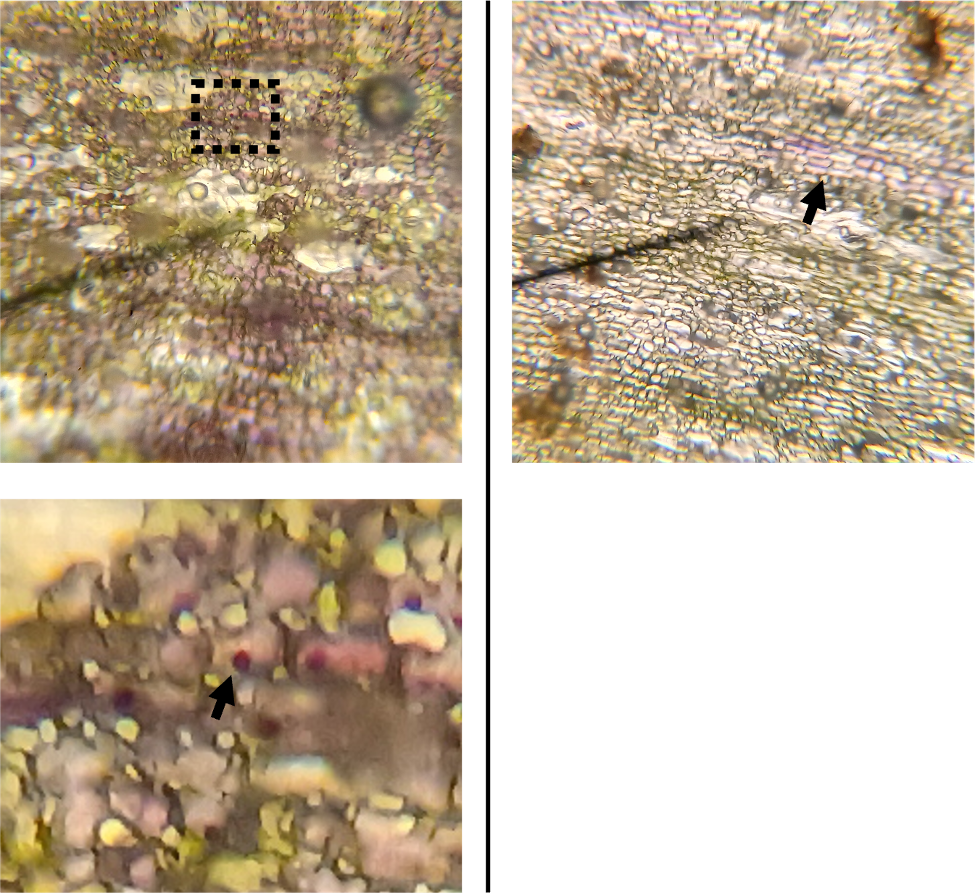

Let’s take a closer look at the stems of each tomato variety. Using a simple light microscope, we can see that anthocyanins accumulate in a fraction of the epidermal cells of Indigo Blue Beauty, forming a sort of patchy pattern (Fig. 4, left top). Apologies for the blurry image! Though it was taken with my phone camera (lol), the biggest reason for the blur is actually trichomes – small hairs – which stick out from the tissue and appear out of focus. There may be a few stray air bubbles in there as well…

Figure 4: Left top: Stem epidermal cells from tomato “Indigo Blue Beauty” at 100X magnification. Left bottom: A zoomed in portion of the same image, showing small, darkly pigmented bodies. Possible AVI’s in tomato epidermal cells? Right: Stem epidermal cells from tomato “Black Krim”.

If we zoom in on the same image (Fig. 4, left bottom), we can see small bodies which appear to contain even greater pigment concentration than the surrounding material. I can’t say for certain what these are – Any thoughts would be appreciated! After doing some reading, I think it is possible that these are either Aromatic Vacuolar Inclusions (AVI’s) or anthocyanoplasts. These are small bodies containing high concentrations of pigment that are usually found within the vacuole of plant cells [22]. For reference, vacuoles are large organelles (often occupying most of a plant cell’s volume) with functions ranging from storage of chemicals to maintenance of turgor pressure, which gives plant tissues structural rigidity. AVI’s/anthocyanoplasts have been observed in a variety of plant species [19], though I have not been able to find any information on these bodies in tomatoes specifically… which is pretty neat! AVI formation has of course been studied in Arabidopsis already [3].

On the right side of Figure 4, we can see that the epidermis of the Black Krim tomato has only a few clusters of cells which contain purple pigment (likely anthocyanins), which explains the lighter color of its stems.

How did the high anthocyanin accumulation in the Indigo Blue Beauty tomato come about? Tracking the ancestry of my tomato plant has proven to be tricky, so take everything here with a grain of salt. From what I can determine, Indigo Blue Beauty is probably the result of a cross between a Blue tomato and Beauty King, bred by Bradley Gates at Wild Boar Farms [24][26]. Blue tomatoes are themselves likely the result of a breeding program run by the Oregon State University, where they acquired their high anthocyanin accumulation traits by crossing domesticated tomatoes with wild relatives [14][18][20]. There are a few different genetic loci which are known to confer the purple fruit trait in tomatoes [14], though sadly I am not entirely sure which is present in my particular plant. Another tomato developed from the same breeding program, Indigo Rose, possesses two such loci, called anthocyanin fruit (Aft) and atroviolacium (atv) [27]. Both loci contain genes encoding for MYB-family transcription factors. Transcription factors are proteins which interact directly with DNA. Their job it is to regulate the expression of other genes (basically, turn them on or off). In the case of Indigo Rose tomatoes, the MYB transcription factors at the Aft and atv loci appear to be involved in the regulation of genes which code for enzymes necessary for anthocyanin production [27].

Anthocyanins in sunflowers:

Behold! Here are two different cultivars of the sunflower (Helianthus annuus) growing outside on the deck (Fig. 5). I’m growing these in 7-gallon pots containing normal potting soil. They’re super easy to grow, provided you can keep them safe from predators (slugs and chipmunks in my case). The variety on the left (“Chocolate Cherry”) has a higher anthocyanin content than the variety on the right (“Autumn Beauty”).

Figure 5: Apex of a Chocolate Cherry sunflower (left) and an Autumn Beauty sunflower (right).

Why should we care? In this case, the high anthocyanin content of the Chocolate Cherry plant is probably a by-product of selection for striking, darker colored flowers. The anthocyanin pigments that give the flowers their deep color are apparently also present at earlier stages in the development of the plant. Unfortunately, my plants haven’t flowered yet. If I can keep them alive long enough (no guarantees!), I’ll try to share a picture of the blooms. Stay tuned.

Why is chocolate cherry more heavily pigmented than its other sunflower brethren? Alas, I could not find any research on this particular sunflower variety. HOWEVER, I did find this paper [12], which identified the HaMYB1 gene, another MYB-family transcription factor (Ack! They’re everywhere!) as a possible regulator of floral anthocyanin accumulation.

Gene of the week!

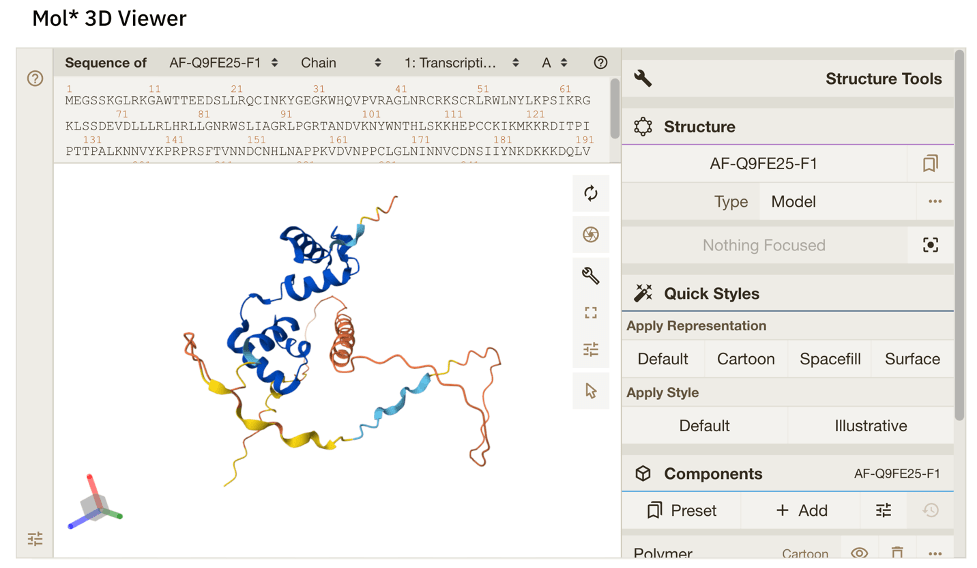

Phew! We’re almost done. That brings us to our final segment… Gene of the Week! This week’s Gene of the Week is, of course, PAP1, aka. MYB75 in Arabidopsis! This gene is located at the AT1G56650 locus on chromosome 1 (denoted by “AT1G” in the locus ID number). The PAP1 protein is yet another MYB-family transcription factor… quelle surprise. The UniProt database indicates that PAP1 is 248 amino acids long and has a mass of ~28 kDa. A predicted protein structure from Alphafold is available (Fig. 6). In it, you can see the part of the protein which is responsible for its interaction with DNA (marked in dark blue, which indicates high confidence in the predicted structure).

Figure 6: Alphafold predicted structure of PAP1/MYB75. Available here at: https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/Q9FE25

As we have seen before, overexpressing PAP1 (such as in the pap1-D line) results in higher anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis [2]. A recent paper presented evidence that PAP1, along with another transcription factor called BZR1, binds to DNA upstream of genes involved in anthocyanin production to regulate their expression [10].

Works Cited:

[1] Ahmad, M., Lin, C., & Cashmore, A.R. (1995). Mutations throughout an Arabidopsis blue-light photoreceptor impair blue-light-responsive anthocyanin accumulation and inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. The Plant Journal 8(5), 653-658. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08050653.x

[2] Borevitz, J.O., Xia, Y., Blount, J., Dixon, R.A., & Lamb, C. (2000). Activation Tagging Identifies a Conserved MYB Regulator of Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis. The Plant Cell 12(12), 2383-2393. DOI: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2383

[3] Chanoca, A., Kovinich, N., Burkel, B., Stecha, S., Bohorguez-Restrepo, A., Ueda, T., Eliceiri, K.W., Grotewold, E., & Otegui, M.S. (2015). Anthocyanin Vacuolar Inclusions Form by a Microautophagy Mechanism. The Plant Cell 27(9), 2545-2559. DOI: 10.1105/tpc.15.00589

[4] Downey, J.M. Measuring infarct size by the tetrazolium method. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from: https://www.southalabama.edu/ishr/help/ttc/

[5] Gould, K.S., Jay-Allemand, C., Logan, B.A., Baissac, Y., & Bidel, L.P.R. (2018). When are foliar anthocyanins useful to plants? Re-evaluation of the photoprotection hypothesis using Arabidopsis thaliana mutants that differ in anthocyanin accumulation. Botany 154, 11-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.02.006

[6] Heijde, M., Binkert, M., Yin, R., Ares-Orpel, F., Rizzini, L., Van De Slijke, E., Persiau, G., Nolf, J., Gevaert, K., De Jaeger, G., & Ulm, R. (2013). Constitutively active UVR8 photoreceptor variant in Arabidopsis. PNAS 110(50), 20326-20331. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1314336110

[7] Khoo, H.E., Azlan, A., Teng Tang, S., Meng Lim, S. (2017). Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food & Nutrition Research 61(1), 1361779. DOI: 10.1080/16546628.2017.1361779

[8] Kliebenstein, D.J., Lim, J.E., Landry, L.G., & Last, R.L. (2002). Arabidopsis UVR8 Regulates Ultraviolet-B Signal Transduction and Tolerance and Contains Sequence Similarity to Human Regulator of Chromatin Condensation 1. Plant Physiology 130(1), 234-243. DOI: 10.1104/pp.005041

[9] Kwon, S., Ahn, I., Kim, S., Kong, C., Chung, H., Do, M., & Park, K. (2007). Anti-Obesity and Hypolipidemic Effects of Black Soybean Anthocyanins. Journal of Medical Food 10(3). DOI: 10.1089/jmf.2006.147

[10] Lee, S., Kim, S., Park, T., Kim, Y., Lee, J., & Kim, T. (2024). Transcription factors BZR1 and PAP1 cooperate to promote anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis shoots. The Plant Cell 36(9), 3654-3673. DOI: 10.1093/plcell/koae172.

[11] Li, Z., & Ahammed, G.J. (2023). Plant stress response and adaptation via anthocyanins: A review. Plant Stress 10, 100230. DOI: 10.1016/j.stress.2023.100230

[12] Ma, Z., Zhou, H., Ren, T., Yu, E., Feng, B., Wang, J., Zhang, C., Zhou, C., & Li, Y. (2024). Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis revealed that HaMYB1 modulates anthocyanin accumulation to deepen sunflower flower color. Plant Cell Reports 43, Article number 74. DOI: 10.1007/s00299-023-03098-3

[13] Mattioli, R., Francioso, A., Mosca, L., & Silva, P. (2020). Anthocyanins: A Comprehensive Review of their Chemical Properties and Health Effects on Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 25(17), 3809. DOI: 10.3390/molecules25173809

[14] Mes, P.J., Boches, P., Myers, J.R., & Durst, R. (2008). Characterization of Tomatoes Expressing Anthocyanin in the Fruit. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 133(2), 262-269. DOI: 10.21273/JASHS.133.2.262

[15] Murchie, E.H., & Lawson, T. (2013). Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: a guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. Journal of Experimental Botany 64(13), 3983-3998. DOI: 10.1093/jxb/ert208

[16] Nakabayashi, R., Yonekura-Sakakibara, K., Urano, K., Suzuki, M., Yamada, Y., Nishizawa, T., Matsuda, F., Kojima, M., Sakakibara, H., Shinozaki, K., Michael, A.J., Tohge, T., Yamazaki, M., & Saito, K. (2013). Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. The Plant Journal 77(3), 367-379. DOI: 10.1111/tpj.12388

[17] National Center for Biotechnology Information (2025). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 154723842, Nasunin. Retrieved July 27, 2025 from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Nasunin.

[18] Oregon State University. The Purple Tomato FAQ. Retrieved July 27, 2025 from: https://horticulture.oregonstate.edu/oregon-vegetables/purple_tomato_faq

[19] Pecket, R.C., & Small, C.J. (1980). Occurrence, location, and development of anthocyanoplasts. Phytochemistry 19(12), 2571-2576. DOI: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83921-7

[20] Pinetree Garden Seeds (2025). Blue Beauty Tomato (Organic 80 Days). Retrieved July 27, 2025 from: https://www.superseeds.com/products/blue-beauty-tomato?srsltid=AfmBOoq9aMdEUZPMm_ByX7U1yF6bACgPTLnKnbWxmIZbh9SJFmK-61Pr

[21] Pokorny, K., & Myers, J. (2023). OSU breeding program produced series of purple tomatoes with healthy antioxidants. Retrieved July 27, 2025 from: https://news.oregonstate.edu/news/osu-breeding-program-produced-series-purple-tomatoes-healthy-antioxidants

[22] Pourcel, L., Irani, N.G., Lu, Y., Riedl, K., Schwartz, S., & Grotewold, R. (2010). The formation of Anthocyanic Vacuolar Inclusions in Arabidopsis thaliana and implications for the sequestration of anthocyanin pigments. Molecular Plant 3(1), 78-90. DOI: 10.1093/mp/ssp071

[23] Wolff, K., & Pucker, B. (2025). Dark side of anthocyanin pigmentation. Plant Biology (early issue). DOI: 10.1111/plb.70047

[24] Tomato seeds, Blue Beauty. Retrieved July 27, 2025 from: https://www.rareseeds.com/tomato-blue-beauty?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=20736059190&utm_content=&utm_term=&campaign_name=%7bcampaignname%7d&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=20742381038&gbraid=0AAAAAD-y-J_jFQ7Lt95ApSeCYniENGYzY&gclid=Cj0KCQjw-ZHEBhCxARIsAGGN96KEDYjoJ-Vj-5mPwnphXwIxDBbjK3LPjuhsck3gfrWENxBDCC5I4wEaAkG8EALw_wcB

[25] Toufektsian, M., de Lorgeril, M., Nagy, N., Salen, P., Donati, M.B., Giordano, L., Mock, H., Peterek, S., Matros, A., Petroni, K., Pilu, R., Rotilio, D., Tonelli, C., de Leiris, J., Boucher, F., & Martin, C. (2008). Chronic Dietary Intake of Plant-Derived Anthocyanins Protects the Rat Heart against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. The Journal of Nutrition 138(4), 747-752. DOI: 10.1093/jn/138.4.747

[26] Wild Boar Farms (2017). Blue Beauty: 100 PK. Retrieved July 27, 2025 from: https://www.wildboarfarms.com/product/blue-beauty-100-pk/

[27] Yan, S., Chen, N., Huang, Z., Li, D., Zhi, J., Yu, B., Liu, X., Cao, B., & Qiu, Z. (2019). Anthocyanin Fruit encodes an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, SlAN2-like, activating the transcription of SlMYBATV to fine-tune anthocyanin content in tomato fruit. New Phytologist 225, 2048-2063. DOI: 10.1111/nph.16272

EDIT: My chocolate cherry sunflower has flowered! Pictured with an autumn beauty sunflower in the background. 🙂

Leave a comment