You may have noticed that there was a large gap between this post and the last. My apologies. I’m increasingly busy, and so my posts will unfortunately be more sporadic from now on. But fear not, the releases shall continue! They’ll be special occasions… think Christmas, but not as good.

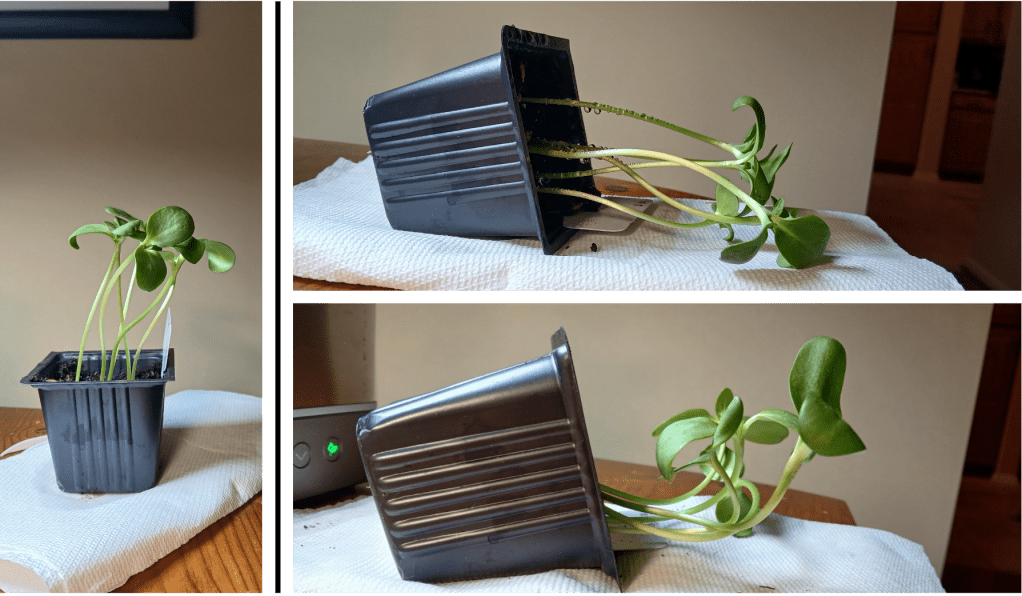

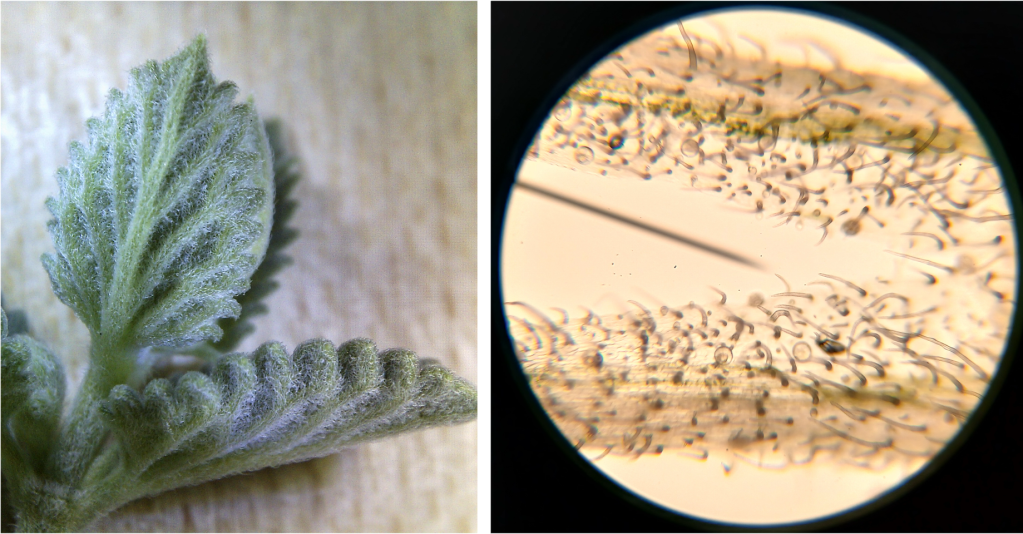

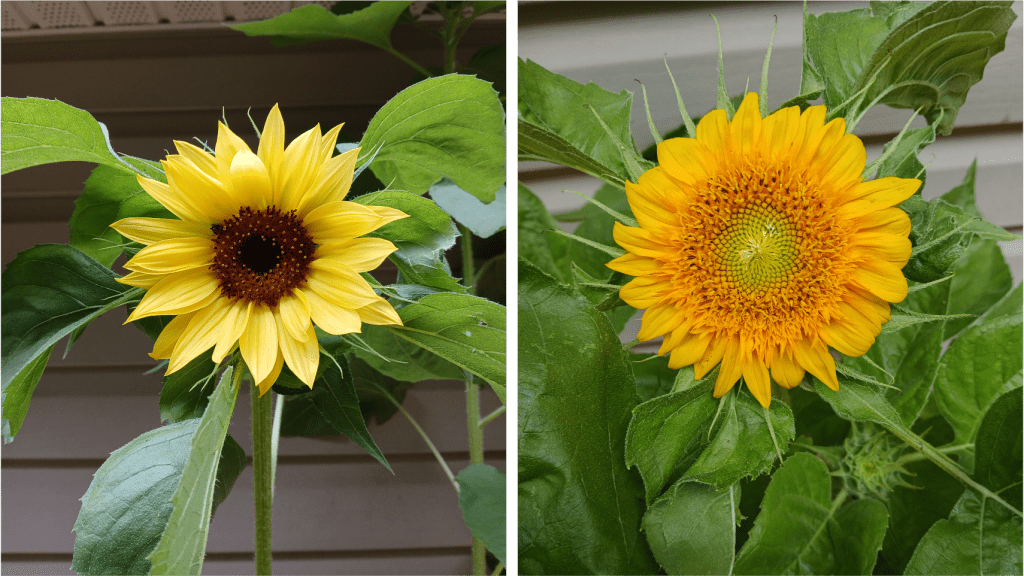

Anyway, I recently acquired these lovely lithops plants at a local garden center (Figure 1 left). The name “lithops” is derived from the Greek word for “stone”, because they look like kind of like pebbles when viewed from above. They’re definitely weird looking. I rather like them, but some of my relations commented that they look like toes. Now I can’t unsee that. **shudders**.

Lithops is a genus of succulents native to southern Africa. Because they are popular houseplants, you should be able to find tons of information about their care and growth habits online. There are also already a few excellent blogs about lithops biology (easily found via google search). Therefore, in order make this blog post a bit more unique, I will be using my light microscope to look at some of their more interesting features up-close! So, read on if you want to see lithops in more detail than you would ever reasonably need to.

An aside: I’ve never seen lithops in the wild, but I noticed while looking through some old pictures that I’d inadvertently photographed one of their relatives in the Canary Islands years ago. Both lithops and the ice plant (Figure 1 right) are members of the family Aizoaceae. And they’re both unusual in their own right!

Figure 1. Left: An unidentified lithops (possibly L. karasmontana?) plant currently inhabiting our hallway. Right: an ice plant (Mesembryanthem sp.) photographed on the Canary Islands. They don’t look very much alike, do they? Try looking for images of their flowers… that might clear things up for you.

Ok, seriously, what am I looking at here?

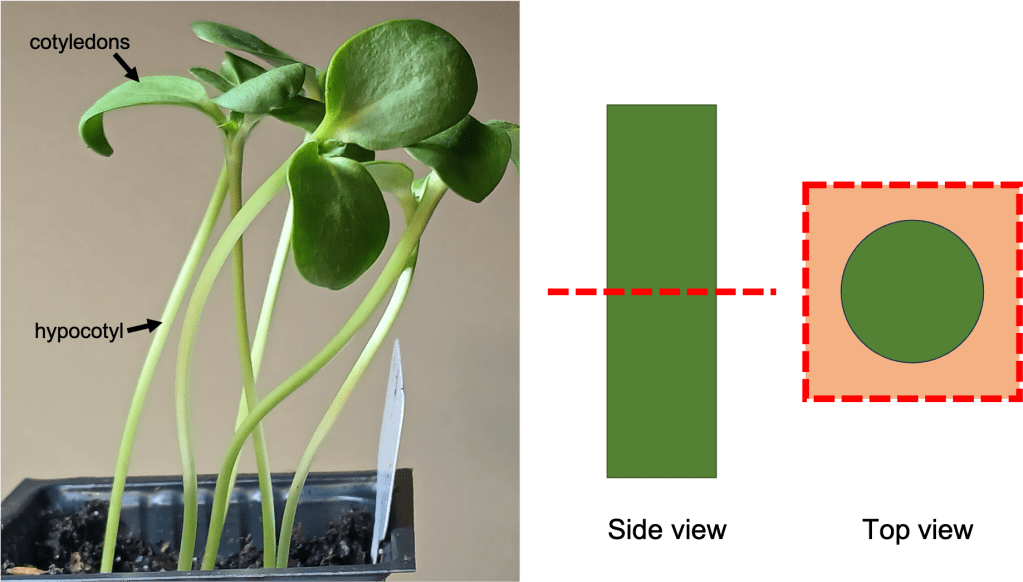

Looking at Figure 1, it’s probably obvious to you that lithops have a fairly unusual anatomy. They barely look like plants at all! So, when we look at a lithops, what are we really seeing?

Basically, the part of the plant that we can see is made up of two succulent leaves that are fused together at the base. The other parts of the plant, such as new pairs of leaves and the meristematic tissue that generates them, are hidden inside (see Figure 2 below, or source [6] for a photograph of a dissected lithops).

Figure 2. Cutaway of a lithops plant to show its internal structure.

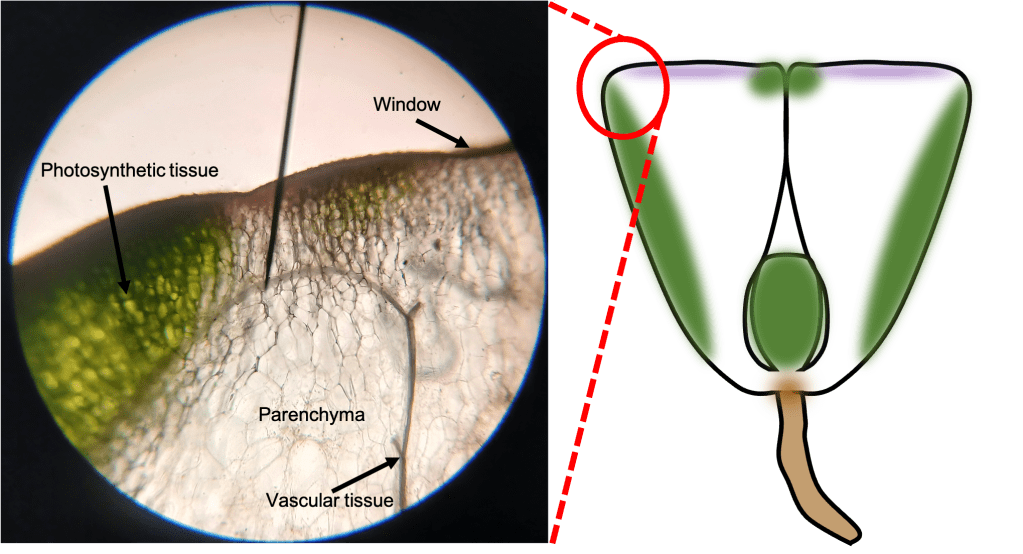

The leaves of the lithops plant have an unusual structure. The green photosynthetic tissue is not visible from the outside; Rather, it lines the inside of the sides of the leaf. The skyward-facing part of the leaf, also known as the “window”, is relatively transparent, allowing sunlight to enter and reach the photosynthetic tissue. Most of the volume of the leaf is taken up by transparent parenchyma tissue, which stores water and allows light penetration.

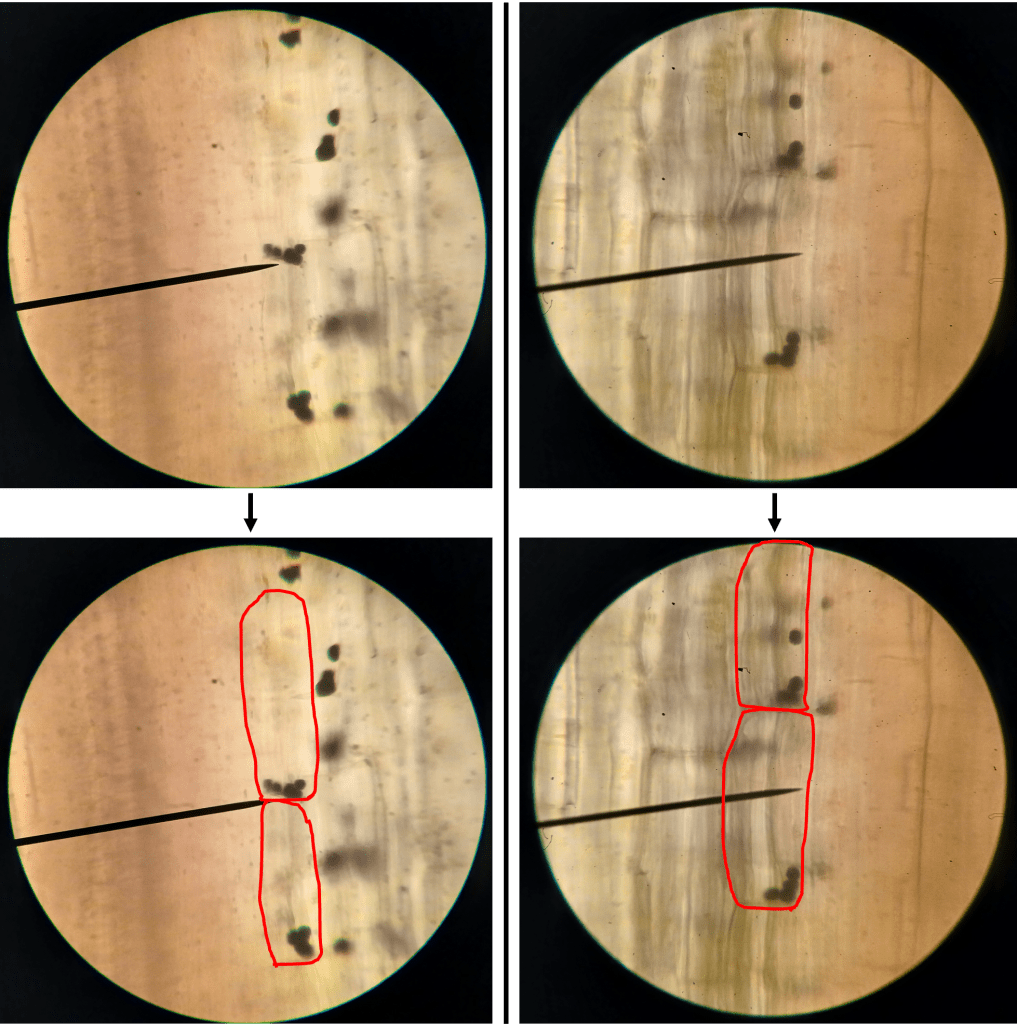

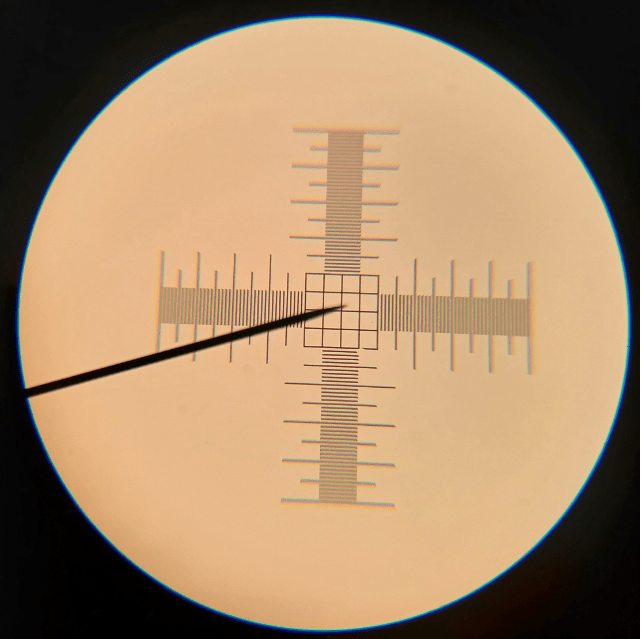

Despite its odd anatomy, when we examine lithops at the cellular level, we can see that it’s really not so different from other plants after all. For example, if we look at the epidermis of the leaf, we can see that it is made up of tightly interlocking epidermal cells punctuated by pores known as stomata (Figure 3). We’ll talk more about those in our next blog post (stay tuned!). But for now, just know that these structures are found in virtually all land plants and are required for gas exchange between the leaf and its environment (O2 and CO2 for respiration and photosynthesis, respectively).

Figure 3. Closeup of the lithops epidermis (400X), showing epidermal cells and an individual stoma. Stomata are themselves made up of two guard cells, which surround a central pore.

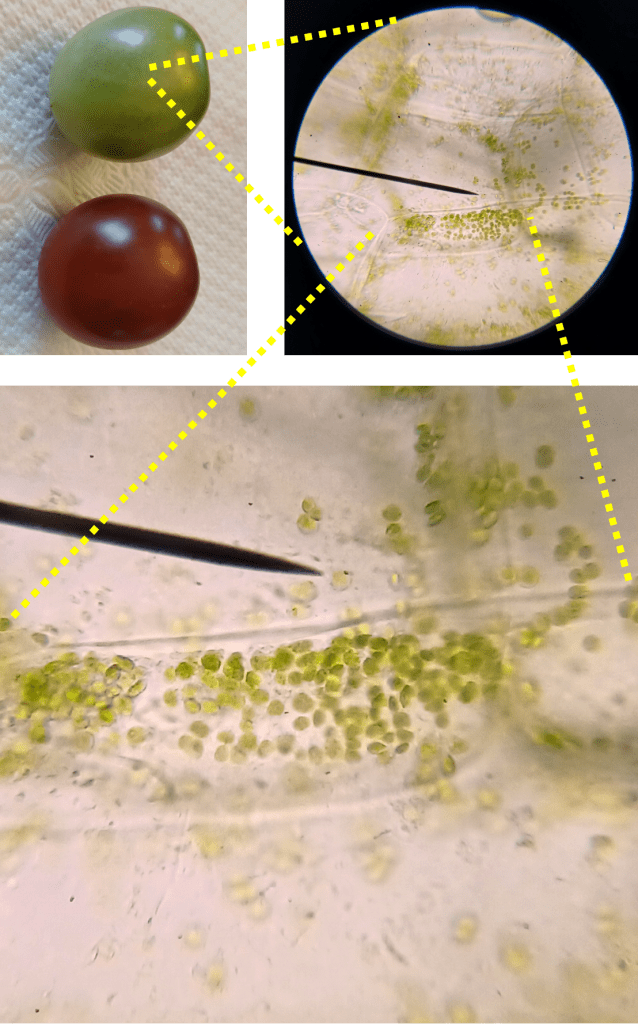

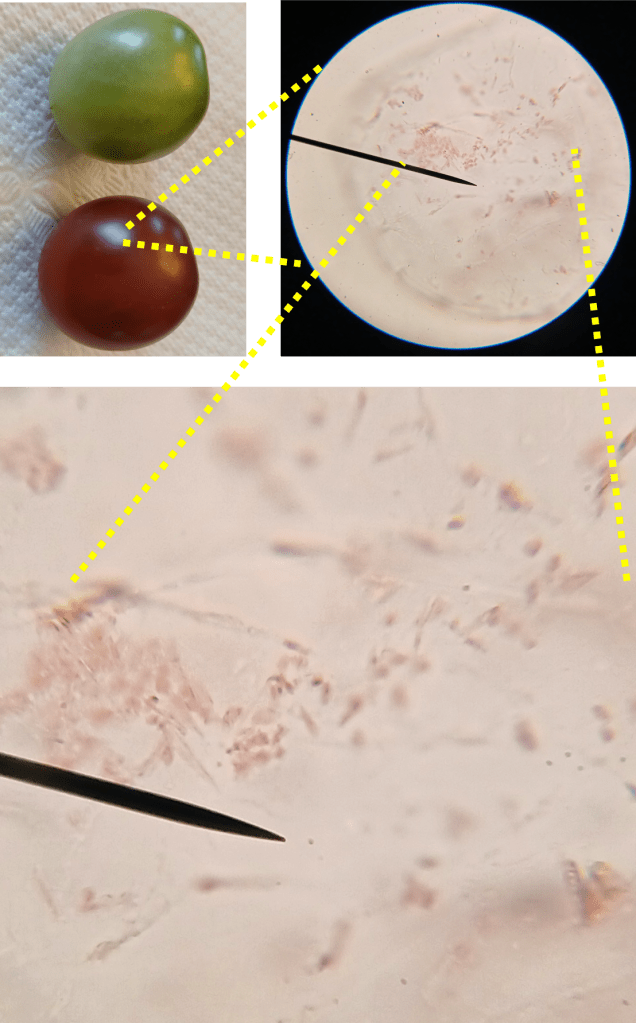

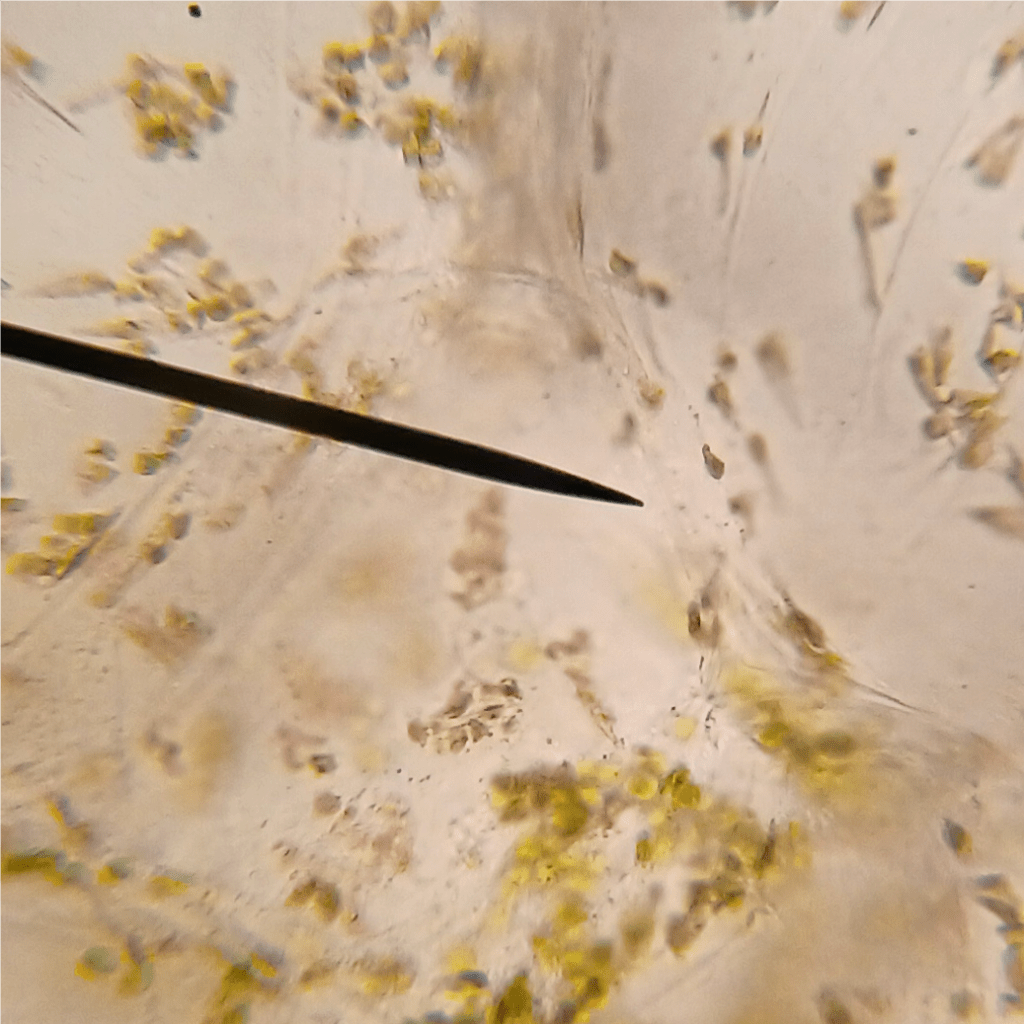

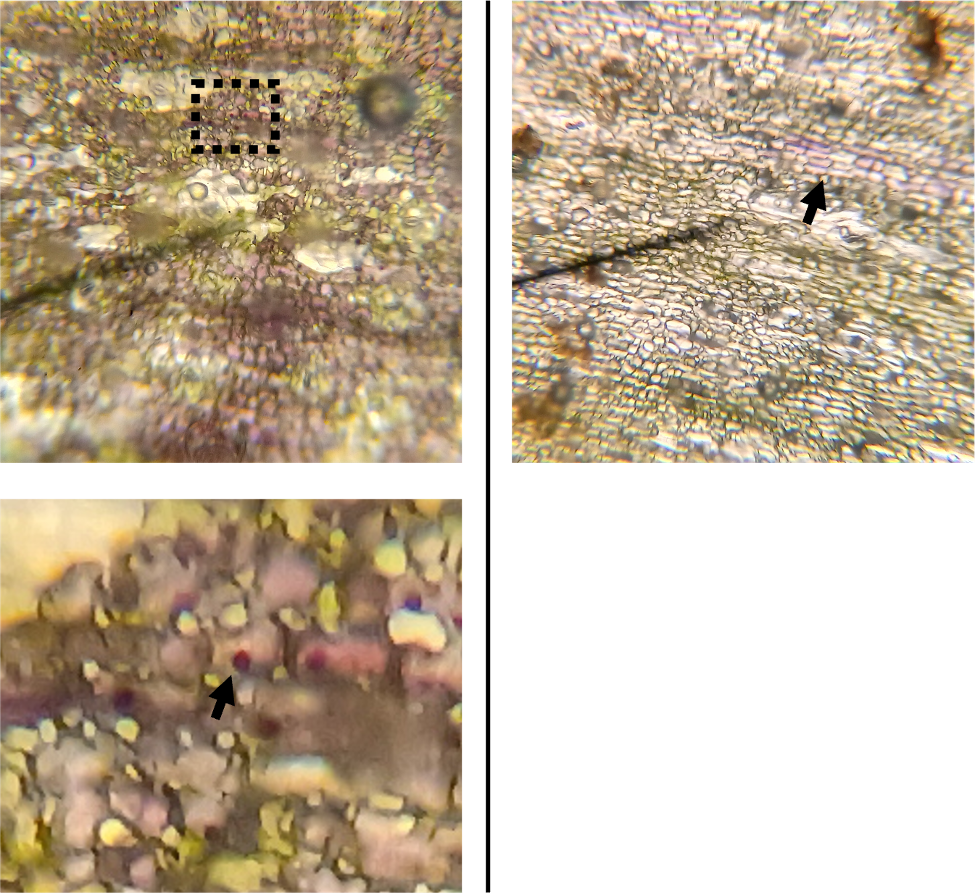

If we cut into a leaf and examine some of the green tissue, we can see that there is a layer of photosynthetic cells which are by traversed by a network of vascular tissue (Figure 4). Taking a closer look at the photosynthetic cells, we can see that there are abundant chloroplasts, which give them their green color (Figure 4 bottom left). If we look more closely at the vascular tissue, we can see intricate reticulations which are characteristic of xylem, which transports water (Figure 4 bottom right). This is all pretty textbook plant stuff, nothing unusual to see here.

Figure 4. Closeup of lithops green tissue. Top right: A zoomed-out image of a section of green tissue. Bottom left: 400X image of photosynthetic cells, showing chloroplasts. Right: 400X image of vascular tissue.

Finally, if we take a transverse section of a leaf, we can observe the transition from the green photosynthetic tissue on the side to the clear tissue of the window on the top (Figure 5). The lack of pigmentation in the cells directly below the window allows sunlight to enter the leaf. However, I did notice a slight purple tinge in this region – this is possibly due to the presence of anthocyanins, which may help protect delicate structures within the leaf from harmful radiation [2]. In Figure 5, we can also observe the water-storing parenchyma cells. These cells lack pigment, and are super-ginormous (technical term).

Figure 5. Transverse section of a lithops leaf, showing several different parts: photosynthetic tissue, window, and parenchyma tissue.

“How many are there?! 36, counted them myself…”

The classification of species within the Lithops genus is a bit of a complicated affair. As of 2011, there were actually 37 recognized species of lithops [3], though this number is not set in stone. One problem is that different species of lithops are difficult to tell apart by eye. This is partly due to considerable variation in morphology even within individual species. As such, the grouping of lithops populations into species is subject to potential revision. For example, a genetic study in 2019 determined that L. amicorum was not its own distinct species, but was actually a sub-population of L. karasmontana [5]. (So perhaps there are 36 species now, eh?)

Genome sequencing would surely enable more robust phylogenetic analysis within the Lithops genus. Unfortunately, I could not find any publicly available Lithops genomes by searching the NIH genomes database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/home/genomes/). There appear to be two Lithops genome sequencing projects currently in the works: Lithops lesliei (Iridian Genomes) and Lithops karasmontana (Kew Gardens), but there isn’t much available information from either of these projects yet (although Kew does have some annotated gene sequences for L. karasmontana available on the tree of life: https://treeoflife.kew.org/specimen-viewer).

Of course, genome sequencing is not a trivial exercise; Furthermore, to look at relationships between species, you would need to do it many times over. If only there were a more efficient way to assess the genetic differences between distinct populations of lithops!

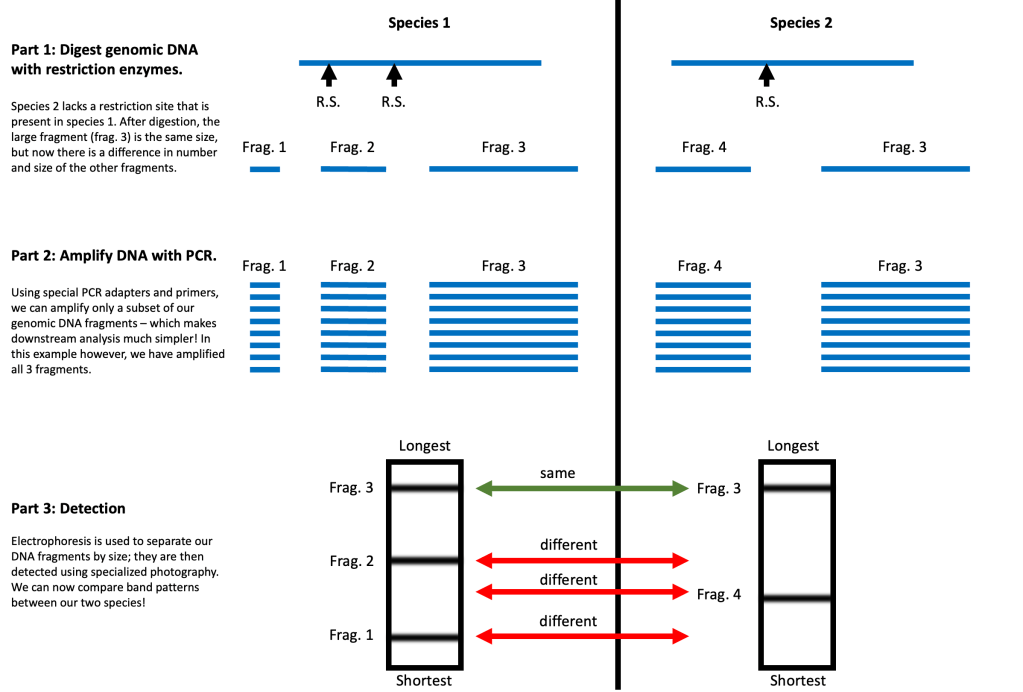

The two studies that I cited above [3][5] do just that, using something called AFLP markers (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphisms). But what the heck are AFLP markers? Fortunately, the name “AFLP” is fairly descriptive. AFLP’s allow you to differentiate between populations by assessing the Lengths of Amplified Fragments. Er…

When we say “Fragments”, we are referring to pieces of DNA. You can generate DNA fragments by digesting genomic DNA with restriction enzymes – which cut the DNA in a sequence-specific manner. This produces many fragments of variable lengths. Genomic DNA from different species varies in the location and number of restriction sites, and so will generate fragments of different sizes.

When we say “Amplified”, we mean that the DNA fragments have been amplified using a technique called PCR. Basically, PCR allows you to take tiny amount of DNA and copy it over and over again until it can be easily detected. Amplified DNA fragments are then sorted by size using a technique called electrophoresis, and are subsequently detected using specialized photography. Advanced statistical techniques are then used to assess the similarity between species on the basis of the sizes of many DNA fragments simultaneously.

A more detailed explanation of AFLP markers is beyond the scope of this blog, but I’ve added a grossly over-simplified diagram below to make the concept easier to visualize. I’ll also direct you to this short article, which explains AFLP’s better than I ever could: [1]. But the take-home message is this: AFLP markers have enabled researchers to explore the genetic relationships between Lithops species without the need for genomic sequencing. And that’s a wonderful thing!

Figure 6. Simplified overview of AFLP marker analysis to assess the genetic similarity between two species.

Gene of the week/month/or something:

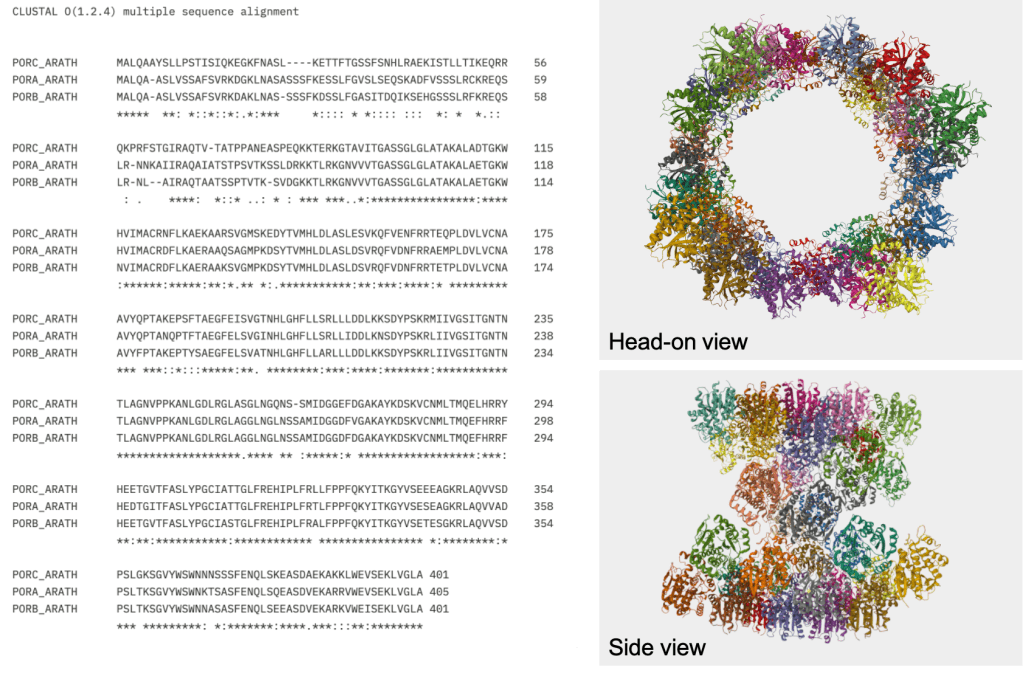

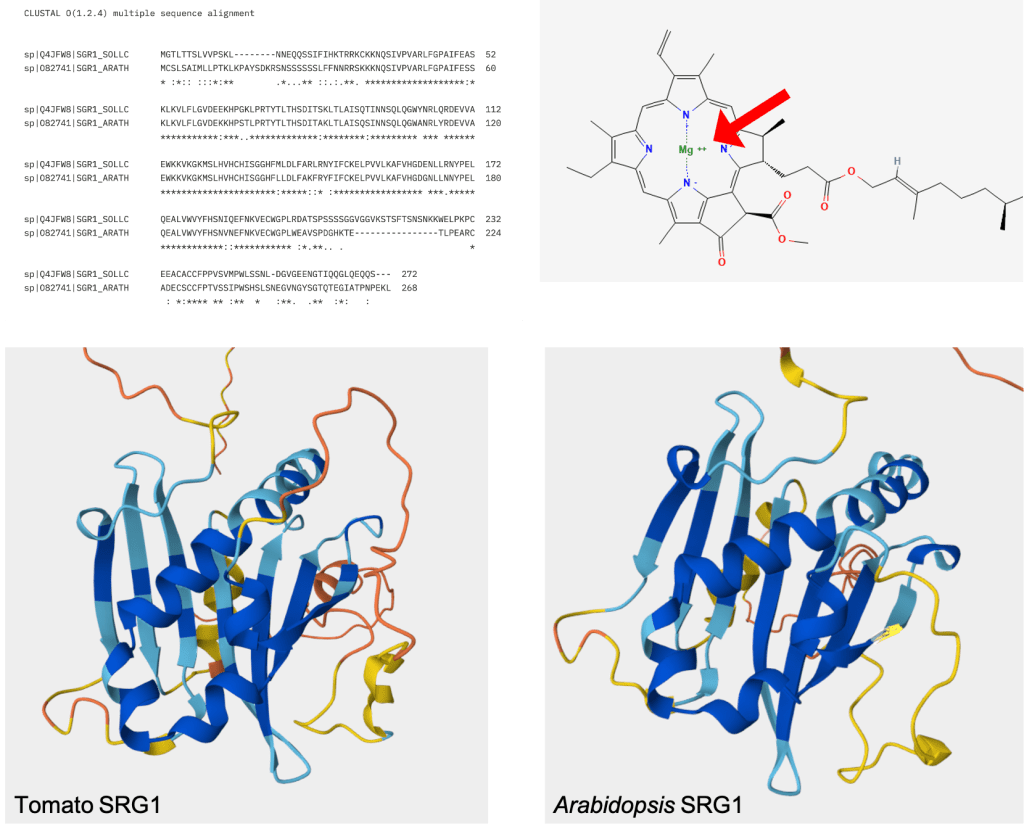

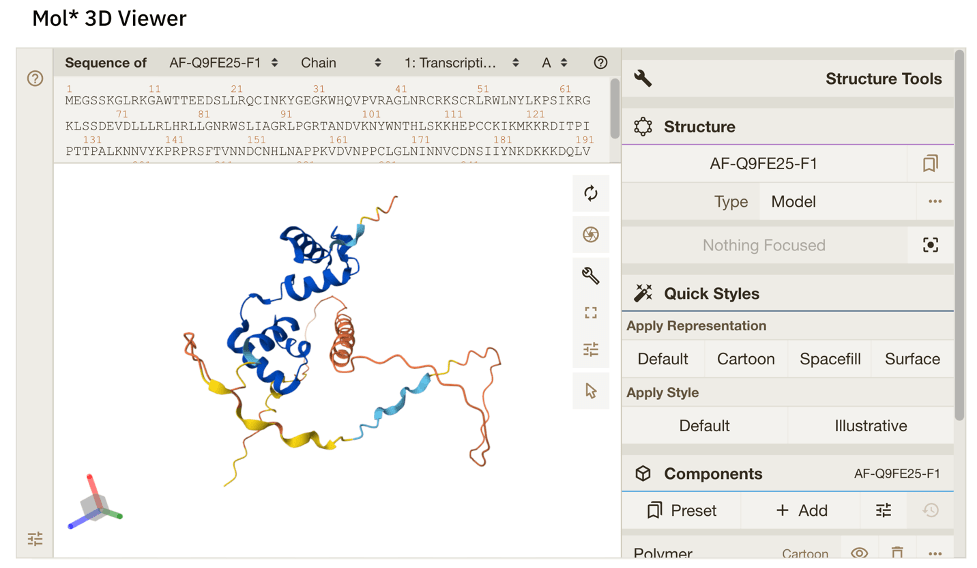

Let’s conclude this first exciting installment of our “Lithops” series with a Gene of the Week! As I pointed out earlier, there are not annotated genomes available for Lithops, and the functions of individual genes in Lithops have not really been explored. Because of this, I thought I’d just pick a random L. karasmontana gene sequence from the Kew Tree of Life dataset (https://treeoflife.kew.org/tree-of-life/6889) and have a bit of fun with it!

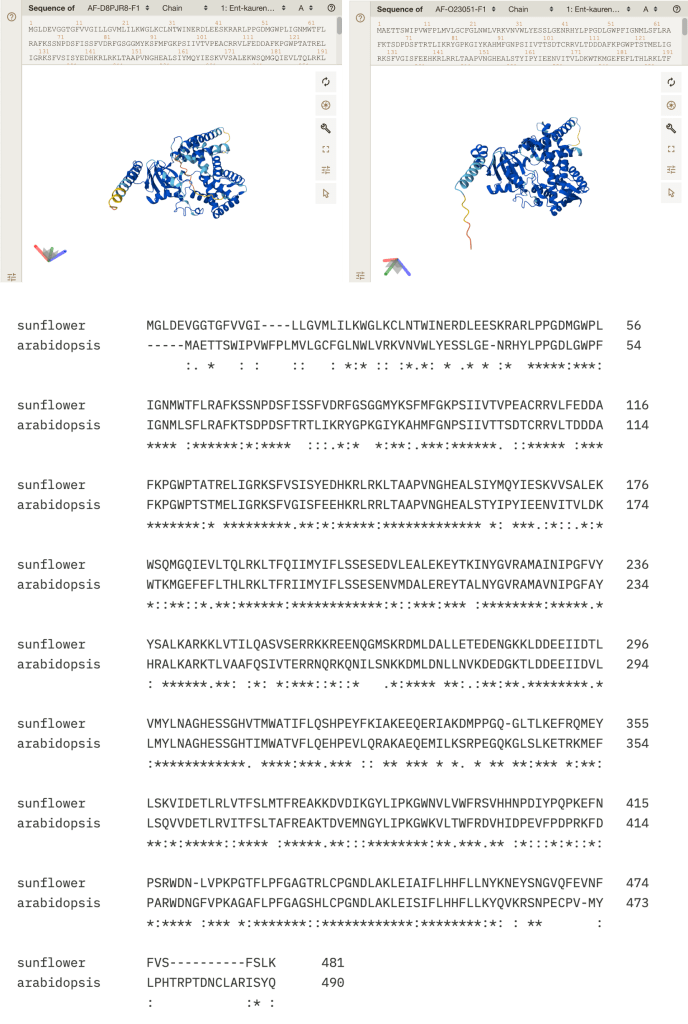

The gene I’ve picked (drumroll please) is… UVH6! More precisely, this is a Lithops ortholog of the UVH6 gene in Arabidopsis. There isn’t much we can infer about the Lithops gene with the information we have. All I can say is that there is a DNA sequence labelled “UVH6” in the Kew dataset, and that it is only a fragment of the total length of the Arabidopsis UVH6 gene (at 1002 bp long). However, this fragment shares 77% sequence identity with the equivalent region of the Arabidopsis gene, which is pretty good!

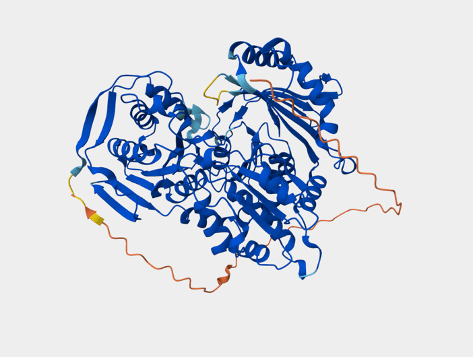

Figure 7. Left: A portion of the Blastn alignment of the putative UVH6 sequence from L. karasmontana (top) and the UVH6 sequence from Arabidopsis (bottom). (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Right: Alphafold predicted structure of Arabidopsis UVH6 protein, because everyone likes pretty pictures (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/AF-Q8W4M7-F1).

Since the UVH6 gene in Lithops has not been studied, we can only infer its possible functions by looking at its homologs in other species, such as Arabidopsis. Based on its homology to well-characterized genes in yeast and humans, the Arabidopsis UVH6 probably codes for a helicase, which is an enzyme which is capable of separating the two strands which make up a DNA double helix [4]. The homologs of UVH6 in humans and in yeast have previously been shown to play important roles in repairing damaged DNA via a process called Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER) [4]. Incidentally, NER is particularly well-suited for repairing DNA lesions caused by exposure to UV radiation; It should come as no surprise, therefore, that Arabidopsis mutant plants which lack a functional UVH6 gene are sensitive (easily damaged) by exposure to UV [4]!

As I said before, we cannot say what the functions of UVH6 in Lithops may be; However, it would be relatively safe to assume that a plant living in regions which receive a lot of sunlight (e.g. lithops) would need mechanisms for DNA repair to prevent themselves from accumulating damage due to exposure to UV. Whether this resilience comes from UVH6 or something else, we cannot say… for now.

Works cited:

[1] Chial, H. (2008). DNA fingerprinting using amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP): No genome sequence required. Nature education 1(1), 176.

[2] Field, K.J., George, R., Fearn, B., Quick, W.P., & Davey, M.P. (2013). Best of both worlds: Simultaneous High-Light and Shade-Tolerance Adaptations within Individual Leaves of the Living Stone Lithops aucampiae. PLoS One 8(10), e75671.

[3] Kellner, A., Ritz, C.M., Schlittenhardt, P., & Hellwig, F.H. (2011). Genetic differentiation in the genus Lithops L. (Rushioideae, Aizoaceae) reveals a high level of convergent evolution that reflects geographic distribution. Plant Biology 13(2), 368-380.

[4] Liu, Z., Hong, S., Escobar, M., Vierling, E., Mitchell, D.L., Mount, D.W., & Hall, J.D. (2003). Arabidopsis UVR6, a Homolog of Human XPD and Yeast RAD3 DNA Repair Genes, Functions in DNA Repair and is Essential for Plant Growth. Plant Physiology 132(3), 1405-1414.

[5] Loots, S., Nybom, H., Schwager, M., Sehic, J., & Ritz, C.M. (2019). Genetic variation among and within Lithops species in Namibia. Plant Systematics and Evolution 305, 985-999.

[6] Sajeva, M. & Oddo, E. (2007). Water Potential Gradients between Old and Developing Leaves in Lithops (Aizoaceae). Functional Plant Science and Biotechnology 1(2), 366-368.