Supertall

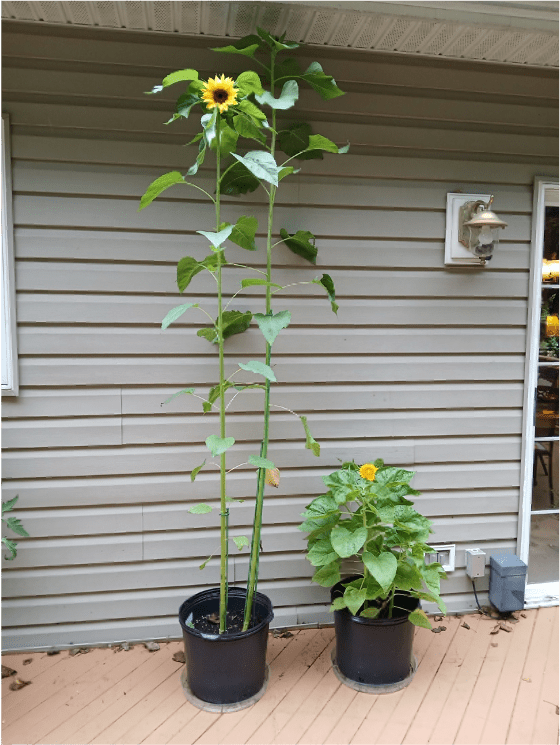

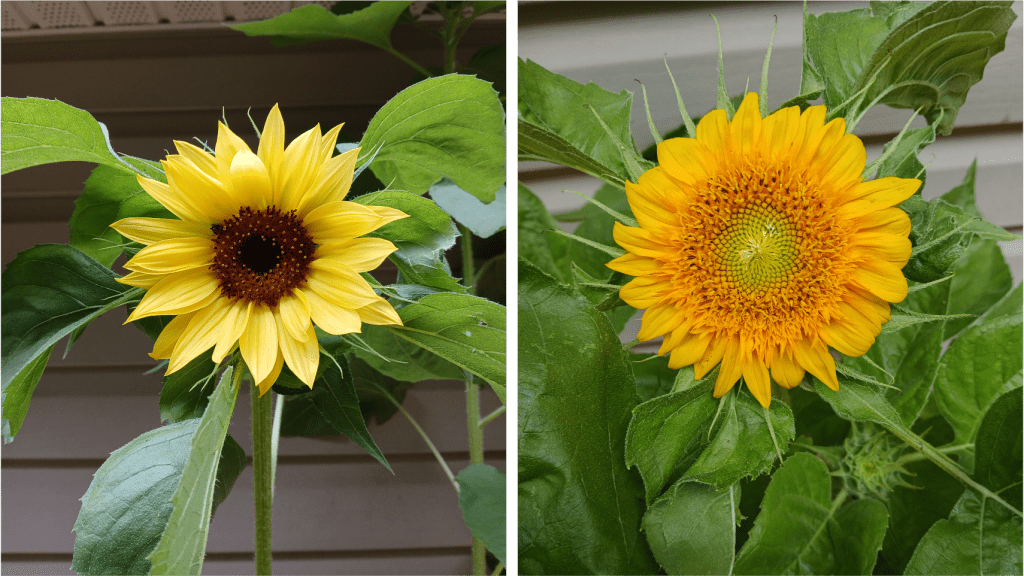

This week I’d like to draw your attention to these two sunflower varieties I have growing on my deck (Figure 1). Bear in mind that all of these plants belong to the same species of sunflower, Helianthus annuus. The pot on the left contains two individuals of the cultivar “Lemon Queen,” while the pot on the right contains three individuals of the cultivar “Teddy Bear.” Seeds of each variety are easily acquired if you want to try growing them yourself.

These plants are the same age and have been growing in the same conditions in the same type of soil. Lemon Queen is a typical height for a sunflower plant. So why the heck is Teddy Bear so short?? The short answer (hardy har) is that I don’t know precisely why. But the journey that led me to this earth-shattering conclusion was intriguing nonetheless! Join me as we go down a veritable rabbit hole about sunflower plant height.

Figure 1. Sunflower “Lemon Queen” (pot on the left) vs. “Teddy Bear” (pot on the right).

Why are dwarf sunflowers desirable?

There are many varieties of dwarf sunflower available to buy, and they are desirable for a few reasons. Their compact size means that they can be grown when space is limited, and smaller flower heads fit nicely into cut flower arrangements.

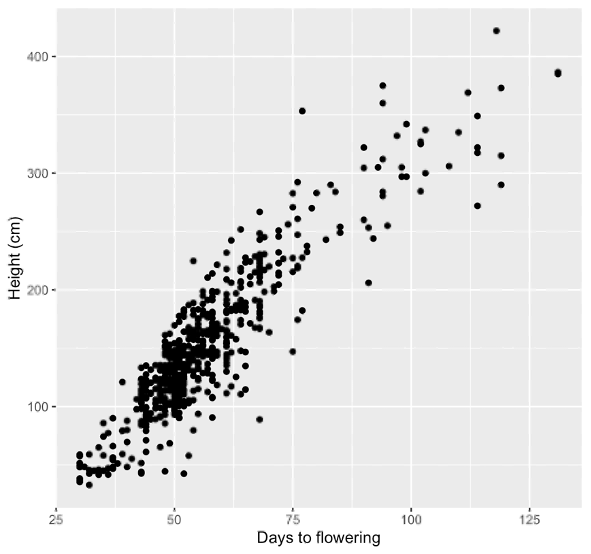

You might wonder whether smaller sunflower varieties mature faster, since they do not need to grow as much before flowering. This is not necessarily the case; My Teddy Bear and Lemon Queen plants flowered at roughly the same age. However, we can address this question more broadly by using the data stored in the HeliantHome database [4]. They have plant height and flowering time data for hundreds of individual plants representing roughly 60 distinct wild populations of Helianthus annuus. Is there a correlation between plant height and flowering? If we plot plant height against flowering time, we can clearly see that there is a strong correlation (Figure 2). From this, we can say that amongst wild populations, sunflower plants that flower earlier tend to be shorter.

There is a caveat, however. It is not clear whether the short plants in this dataset are true dwarf varieties, or whether they are simply short because they were grown in conditions which are not ideal for them. Stress may also affect plant growth and flowering time.

Figure 2. Days to flowering vs. plant height at flowering (cm). Data are taken from the HeliantHome database [4].

Zooooooom!

Sunflowers, like all plants, are made of cells. Therefore, the dramatically short stature of the Teddy Bear sunflower could be due a to 2 factors:

- It could have shorter cells in the stalk, OR…

- It could have less cells overall in the stalk, OR… both!

To see what’s going on here, I peeled some epidermal cells off the stalks of my Lemon Queen and Teddy Bear plants and estimated their height under the microscope. I sampled both Lemon Queen plants and all three Teddy Bear plants.

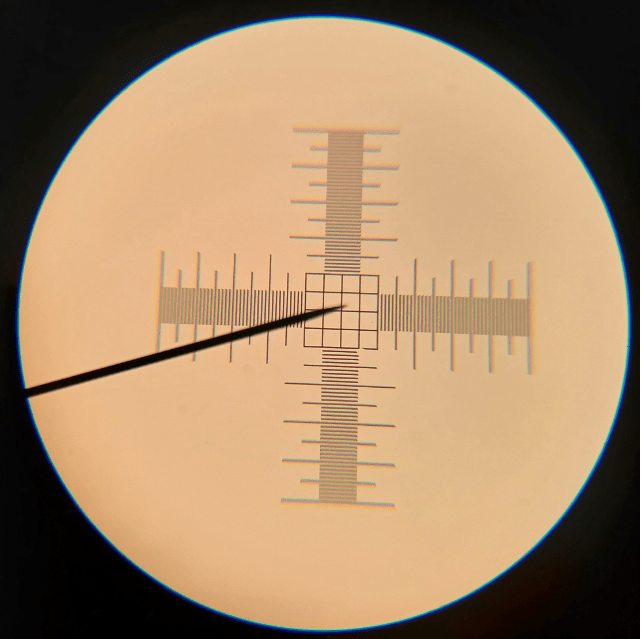

How do we estimate cell height? We use a calibration slide, of course! It’s essentially a tiny ruler printed on a microscope slide that acts as a point of reference for what we’re seeing. It looks like this:

Figure 3. Markings on a calibration slide at 100x magnification. The distance between the smallest lines is 0.01 mm (or 10 µm).

Problem: How do we pick which cells to measure, and how do we measure them? This is admittedly arbitrary. My estimate of average cell height is just that… an estimate. I took the cell samples halfway up the stem of each plant, so the cells were hopefully about the same age. I picked a sample of 10 cells close to my ruler with clearly-defined borders, and I measured their vertical height (See Figure 4, samples are lying horizontally). Length measurements were done using a free image analysis program called FIJI.

Figure 4. Microscopy images of the cells used to estimate cell size in Lemon Queen (Left) and Teddy Bear (Right). Colored bars indicate where length measurements took place.

Table 1: Epidermal cell heights (in µm) in two different sunflower cultivars.

| Lemon Queen | Teddy Bear | |||

| Plant 1 | Plant 2 | Plant 1 | Plant 2 | Plant 3 |

| 92.65 | 57.136 | 113.089 | 60.331 | 46.901 |

| 58.897 | 100.755 | 47.67 | 42.058 | 36.073 |

| 63.24 | 73.018 | 43.852 | 39.685 | 39.913 |

| 80.936 | 65.047 | 62.278 | 61.124 | 56.272 |

| 61.069 | 66.652 | 67.665 | 84.914 | 40.693 |

| 66.948 | 53.947 | 69.215 | 57.141 | 29.698 |

| 87.076 | 48.388 | 106.104 | 54.761 | 50.006 |

| 73.533 | 76.945 | 63.816 | 72.213 | 46.094 |

| 73.529 | 69.806 | 83.095 | 69.039 | 35.938 |

| 75.014 | 79.325 | 73.042 | 34.916 | 67.192 |

| AVERAGE cell height across all plants (µm): | 71.196 | 58.493 | ||

While there might be a slight difference, I wouldn’t say that Teddy Bear has dramatically smaller cells than Lemon Queen. In fact, the arbitrary nature of my sampling method does not give me fabulous confidence that this difference is meaningful at all. Based on this, I would say that the reduced height of Teddy Bear plants is almost entirely due to a smaller number of cells.

Just for fun: My Lemon Queen plants clocked in at an average height of 81.25 inches (2,063,750 µm), and my Teddy Bear plants had an average height of 19.33 inches (490,982 µm). Using our average values for cell height (see Table 1), we find that our average Lemon Queen plant is ~29,000 epidermal cells tall, while the average Teddy Bear plant is just ~8,000 epidermal cells tall.

What genetics cause dwarfism in sunflowers?

Surprisingly, I could only find one study which definitively identifies a genetic cause for dwarfism in sunflowers. Fambrini et al. determined that a loss-of-function mutation in a gene called HaKAO1 results in sunflower plants with an extreme dwarf phenotype [3]. HaKAO1 codes for an enzyme which helps to produce hormones called gibberellins; Without it, plants produce less gibberellins, and do not grow as large [3]. However, the phenotype of their mutant line (called “dw2”) was much more extreme than the dwarfism we see in Teddy Bear plants. Furthermore, a defining feature of the dw2 mutant is small cell size, which Teddy Bear lacks (see above). Therefore, a mutation in HaKAO1 is unlikely to be responsible for the short stature of Teddy Bear sunflowers.

Without a direct source to tell me why Teddy Bear sunflowers are short, I had to resort to more desperate measures. One idea I had was to look for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) which include Teddy Bear in their sampling population. What is GWAS? Basically, we look at variable genetic elements in a large group of individuals, then we look at a phenotype (for example, height) in these individuals, and finally we look for statistically significant associations between particular genetic variants and the phenotype. Doing this allows us to pinpoint specific genetic loci which might affect our phenotype of interest, which we can then test in further experiments.

One common kind of variable genetic element used for GWAS is the SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism). SNPs occur when a single DNA base pair is exchanged for another one. For example, in a hypothetical DNA sequence ATGCATC (only one strand shown), replacing the middle “C” with a “G” (like this: ATGGATC) constitutes a SNP. SNPs are handy because they are easy to detect, and because they are very common in many genomes, giving good coverage.

So anyway, my first idea was… look for GWAS studies which examine sunflower height… then check if Teddy Bear was used in their sampling population… then check whether Teddy Bear has any SNPs which strongly correlate with height! I could only find two sources of GWAS data which examined sunflower plant height. The first source was a dataset published by Delen et al. (2024) [2], and the second source was a dataset published by Todesco et al. (2020) and linked through to HeliantHome [7]. But neither dataset had Teddy Bear in their sampling population! Nuts.

Figure 5: These plots are taken directly from the EasyGWAS page, which represents the Todesco GWAS dataset [7]. Top: Manhattan plot showing position of SNPs on sunflower chromosome 7 (x-axis) and statistical association of these SNPs with plant height (y-axis). One SNP with a statistically significant association with height is highlighted by the red arrow. Bottom: Distributions of plant height for plants with different variations at the SNP locus identified in the Manhattan plot above. Plants with the G/G allelic combination tend to be shorter than those with T/T or G/T.

OK, what now? Well, the Delen and Todesco datasets give us a set of SNPs which have a strong correlation with plant height. A genome assembly for Teddy Bear is not available. But there might be SNP data for Teddy Bear in another GWAS dataset! In theory, I might be able to use such a dataset to check whether Teddy Bear has any SNPs which are associated with plant height.

Alas, I only found a single GWAS source which contains Teddy Bear; Talukder et al. (2019) [6]. Then I encountered another problem… the genetic maps that Talukder, Delen, and Todesco used to denote the location of their SNPs are different [2][6][7]! And reconciling different genetic maps is no trivial task, especially if full sequencing data isn’t available. Without more data, my dreams of identifying a possible genetic reason for the Teddy Bear’s short stature have been dashed. I guess we can’t always get what we want. (But seriously, if you have any ideas, help would be greatly appreciated!)

Gene of the week:

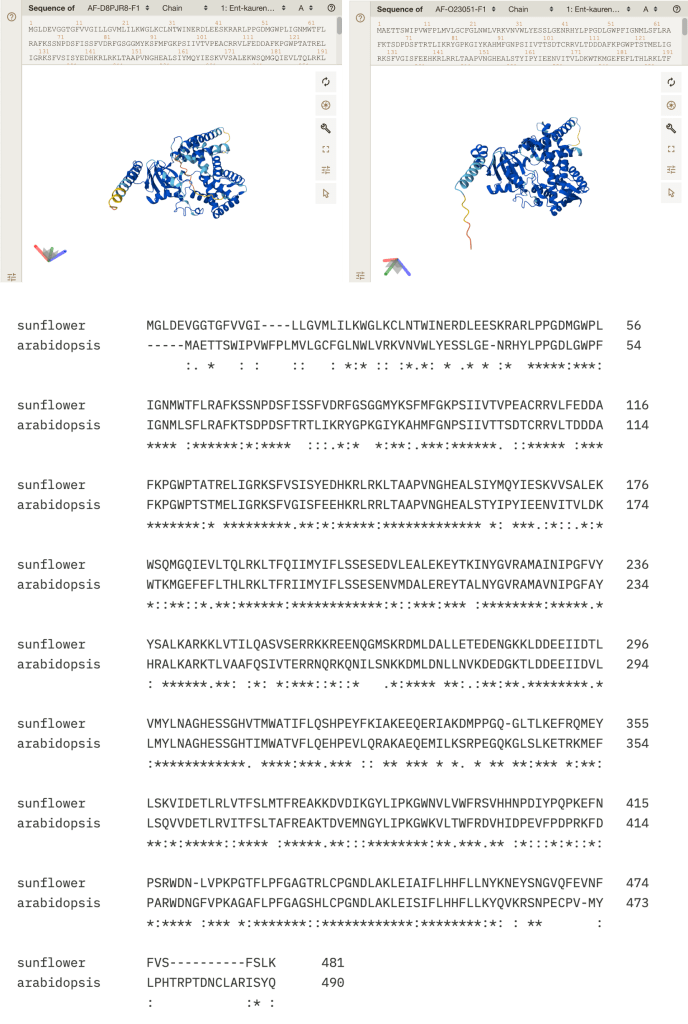

After that rather uninspiring conclusion, let’s now have a little pick-me-up with Gene of the Week ™ ! (EDIT: I’ve been informed that I need to clarify that the trademark is merely a joke, for legal reasons). Since it’s the only gene we really discussed in this post, let’s make this week’s Gene of the Week HaKAO1, or more generally any gene coding for the enzyme ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase. These enzymes catalyze a reaction that is required for the synthesis of gibberellins, which are hormones that control plant development. As previously discussed, a loss-of-function mutation in HaKAO1 is associated with an extreme dwarf phenotype in sunflowers [3]. In the model plant Arabidopsis, a double mutant called kao1 kao2 also displays a marked dwarf phenotype [5]. In this case, mutations in both genes are required to see a phenotype; This is an example of genetic redundancy.

The predicted structure of the KAO1 proteins from sunflower and Arabidopsis are very similar, which is unsurprising since their sequences are so similar (and Alphafold predicts structure based on sequence homology). See Figure 6 below.

Figure 6. Top: Alphafold predicted structures of KAO proteins from sunflower (left) and Arabidopsis (right). The Alphafold models used in this figure may be found at: https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/D8PJR8 and https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/O23051. Bottom: Sequence alignment between sunflower and Arabidopsis KAO1 proteins. The alignment was made using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo?stype=protein) with default parameters.

Epilogue:

If you’re wondering about the name “Teddy Bear,” it comes from the habit of this variety to produce fluffy looking inflorescences. (Sunflowers are actually made up of many individual flowers, which are collectively called an inflorescence). The flowers on the outer edge of a typical sunflower produce large, showy petals, while the flowers in the middle are much smaller by comparison. In Teddy Bear, the middle flowers also produce large, showy petals, giving the “fluffy” appearance. My Teddy Bear isn’t the most spectacular example of this variety, but the unusual inflorescence phenotype can still be seen in Figure 7 below.

Researchers have actually identified the gene responsible for the inflorescence phenotype of Teddy Bear as HaCYC2c, which codes for a transcription factor that promotes the formation of flowers with large petals [1]. In varieties with the “fluffy” phenotype, the DNA sequence that lies upstream of the protein-coding sequence of the HaCYC2c gene is altered. This causes HaCYC2c to be expressed throughout the whole inflorescence rather than simply in the flowers on the edge… giving us “fluffy” flowers [1]!

Figure 7. The inflorescence of Lemon Queen (left) vs. the inflorescence of Teddy Bear, right.

I should point out that some varieties which have the same “fluffy” inflorescence structure as Teddy Bear, such as “Sungold Tall,” do not have the dwarf phenotype. Hence, the alteration at the HaCYC2c locus cannot explain the short stature of the Teddy Bear sunflower.

Works Cited:

[1] Chapman, M.A., Tang, S., Draeger, D., Nambeesan, S., Shaffer, H., Barb, J.G., Knapp, S.J., & Burke, J.M. (2012). Genetic Analysis of Floral Symmetry in Van Gogh’s Sunflowers Reveals Independent Recruitment of CYCLOIDEA Genes in the Asteraceae. PLoS Genetics 8(3), e1002628. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002628

[2] Delen, Y., Palali-Delen, S., Xu, G., Neji, M., Yang, J., & Dweikat, I. (2024). Dissecting the Genetic Architecture of Morphological Traits in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Genes 15(7), 950. DOI: 10.3390/genes15070950

[3] Fambrini, M., Mariotti, L., Parlanti, S., Picciarelli, P., Salvini, M., Ceccarelli, N., & Pugliesi, C. (2011). The extreme dwarf phenotype of the GA-sensitive mutant of sunflower, dwarf2, is generated by a deletion in the ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase1 (HaKAO1) gene sequence. Plant Molecular Biology 75, 431-450. DOI: 10.1007/s11103-011-9740-x

[4] HeliantHome: A public and centralized database. Home of a comprehensive collection of phenotypes for different Sunflower species. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from: http://www.helianthome.org/

[5] Regnault, T., Davière, J., Heintz, D., Lange, T., & Achard, P. (2014). The gibberellin biosynthetic genes AtKAO1 and AtKAO2 have overlapping roles throughout Arabidopsis development. The Plant Journal 80(3), 462-474. DOI: 10.1111/tpj.12648

[6] Talukder, Z.I., Ma, G., Hulke, B.S., Jan, C., & Qi, L. (2019). Linkage Mapping and Genome-Wide Association Studies of the Rf Gene Cluster in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and Their Distribution in World Sunflower Collections. Frontiers in Genetics 10, 216. DOI: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00216

[7] Todesco, M., Owens, G.L., Bercovich, N., Légaré, J., Soudi, S., Burge, D., Huang, K., Ostevik, K.L., Drummond, E.B.M., Imerovski, I., Lande, K., Pascual-Robles, M.A., Nanavati, M., Jahani, M., Cheung, W., Staton, S.E., Muños, S., Nielsen, R., Donovan, L.A., Burke, J.M., Yeaman, S., & Rieseberg, L.H. (2020). Massive haploypes underlie ecotypic differentiation in sunflowers. Nature 584, 602-607. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2467-6. GWAS data are available to view at: https://easygwas.biochem.mpg.de/gwas/results/manhattan/view/37d3d070-e7cf-4388-be6d-05be6907d451/

Leave a comment