Prelude:

While I was moving some tomato plants around earlier this week, I couldn’t help but notice that they felt a little… prickly. Ouch! Close examination of tomato plants reveals that they are covered in tiny hair-like structures, which give them this texture (Figure 1). The next time you see a plant, you might also notice that many of them are sort of… fuzzy. Why? Because they’re covered in trichomes! Trichomes are projections of the epidermis – made of living cells – which perform a variety of important functions, including protecting plants against predators, limiting water loss, and shielding plants from solar radiation [6].

Since trichomes are easy to see under the microscope (and make pretty pictures!), I figured that now was as good a time as any to talk a little bit about them.

Figure 1. Large, hair-like trichomes on the stem of a beefsteak tomato plant. Left: Phone camera image; Right: Microscope image at 50X magnification.

Trichomes in tomato:

Now, I’ve spent a lot of time looking at Arabidopsis trichomes under the microscope. Why? Because they’re large single cells, transparent, and have particularly ginormous nuclei, possibly as a result of endoreplication – where DNA is repeatedly copied, but a cell doesn’t divide [5]. All of these traits are great if you want to image nuclei.

Imagine my shock when I looked at tomato trichomes under the microscope. They’re multicellular – and there is more than one type! Looking back, I really shouldn’t have been surprised at all. Many species of plants have multicellular trichomes, including sunflowers – We’ll talk about those in a minute.

You’re already acquainted with the long, hair-like trichomes in tomato (See Figure 1). What other kinds are there? To have a look, I scraped some epidermal cells off my Indigo Blue Beauty tomato plant and stuck them under the microscope. If you remember my first blog post about anthocyanins, I lamented at the difficulty of getting clear images of epidermal cells under the microscope. All of my images look like Figure 2 left (see below).

Figure 2. Tomato epidermis at 100X magnification. Left and right panels show exactly the same sample; I just changed the focus on the microscope! The tips of glandular trichomes can be seen in the image on the right.

Blech! Why so blurry? The answer is glandular trichomes… they stick upwards out of the epidermis, and out of the plane of focus… which makes everything behind them blurry. By adjusting the focus on our microscope, we can see the ends of the of these trichomes clearly (Figure 2 right). The trichome tips are made of clusters of 4 cells, which sit at the end of a narrow stalk.

I particularly like the image I captured in Figure 3, which shows 3 types of tomato trichomes sitting next to each other. The large hair-like trichome is HUGE and goes way off the end of the picture, while the small hair-like trichome and glandular trichome are tiny by comparison. Despite their enormous size, the large hair-like trichomes are still only one cell thick – and you can see them with the naked eye! Pretty neat. For your reference, the different types of tomato trichomes are nicely summarized by Tissier (2012) [12].

Figure 3. Tomato epidermis imaged at 100X magnification and blown up even further to show detail. From left to right: A large hair-like trichome, a small hair-like trichome, and a glandular trichome can all be seen side-by-side.

Great! So what do all these trichomes actually… do? The predominant idea is that tomato trichomes are primarily for defense against predators such as insects [12], though they may also play a role in water use efficiency and drought tolerance [4]. The hair-like, non-glandular trichomes (NGT’s) form a mechanical barrier to keep insects away from the surface of the plant, and may also damage the digestive systems of insects [11]. I couldn’t find a ton of information about NGT’s in tomatoes specifically, but I did come across this study in a related species, Solanum carolinense, which found that NGT’s impair feeding and weight gain in tobacco hornworm caterpillars [11].

How about the glandular trichomes? I came across this interesting paper which demonstrates that fluid in the glandular trichomes is released as they come into contact with insect foes; The fluid sticks to insects and makes it difficult for them to move [10]. They even have video of this happening in their supplementary data [10]! I highly recommend. Anyway… The glandular trichomes also contain chemicals which inhibit insect feeding. For example, secretions from glandular trichomes are known to elicit stress and starvation responses in aphids [9]. The glandular trichomes in the wild tomato relative Solanum habrochaites produce a compound called zingiberene, which inhibits feeding by aphids [3]. One interesting study crossed this species with domesticated tomato to determine if it would be possible to breed tomatoes with increased aphid resistance [3]. The importance of this research to society is clear; if we want to continue to eat tomatoes en masse, we need to know how to protect them!

Before we move on, I’d just like to muddy the waters a bit with this thought: Tomatoes use trichomes to repel insects that want to eat them. This has an unintended consequence: Predators which eat the insects which eat the tomato may also be repelled by the trichomes!

In the wild, this is less of an issue; The tomato is on its own and needs to protect itself by any means necessary. But when tomatoes are grown domestically, humans give them help in the form of biological pest control – introducing predators to eat the pests. Trichomes may actually make this form of pest control less effective [7]. Therefore, using tomato varieties with lower trichome densities might paradoxically make it easier to control pest populations [7]. However, more work is needed to determine the efficacy of this approach.

Trichomes in sunflower:

Like tomatoes, sunflowers also possess multicellular trichomes of several different varieties. They have large, hair-like trichomes which give mechanical protection (easily visible on the developing head of a Teddy Bear sunflower, see Figure 4 left). They also have much smaller linear glandular trichomes (LGTs) – multicellular structures that resemble tiny strings of pearls (Figure 4 right bottom). As LGTs develop, the nuclei in the cells at the end of the trichome disappear, and these cells start to accumulate terpene compounds [2]. Terpenes are known to have insect repellent properties, implying that LGTs probably play an important role in insect defense [2].

Figure 4. Left: The developing head of a Teddy Bear sunflower is covered in white hairy trichomes. Right top: Sunflower bract at 100X magnification, showing both hairy trichomes and smaller linear glandular trichomes. Right bottom: Close-up of a linear glandular trichome at 400X magnification.

For fun, I also had a look at some trichomes from the stem of my chocolate cherry sunflower (Figure 5). One thing you might notice right away is that the epidermal cells surrounding the hair-like trichomes lack the purple pigmentation found in the rest of the epidermis. I have no clue why this is, but it is interesting! The other observation I made is that the LGT’s often emerge from heavily pigmented areas of the epidermis, but contain no purple pigment themselves. Again, I have no idea why, but it is interesting.

Figure 5. Left: The stem of a chocolate cherry sunflower. Right top: Stem epidermal cells at 100X magnification, showing hair-like NGT’s and comparatively tiny LGT’s. Right bottom: A zoomed-in picture of an LGT protruding out of a heavily-pigmented patch of epidermal cells.

Trichome guests of honor:

This part is just for fun! I have a microscope… and I have a bunch of different plants to look at… so why not just check to see what I can see?

I started with an eggplant plant. It doesn’t have visible hairs; instead, it is covered in a fine white fuzz. Closer examination reveals the presence of stellate (star-shaped) trichomes (Figure 6). They’re pretty crazy looking!

Figure 6. Trichomes from the stem epidermis of an eggplant.

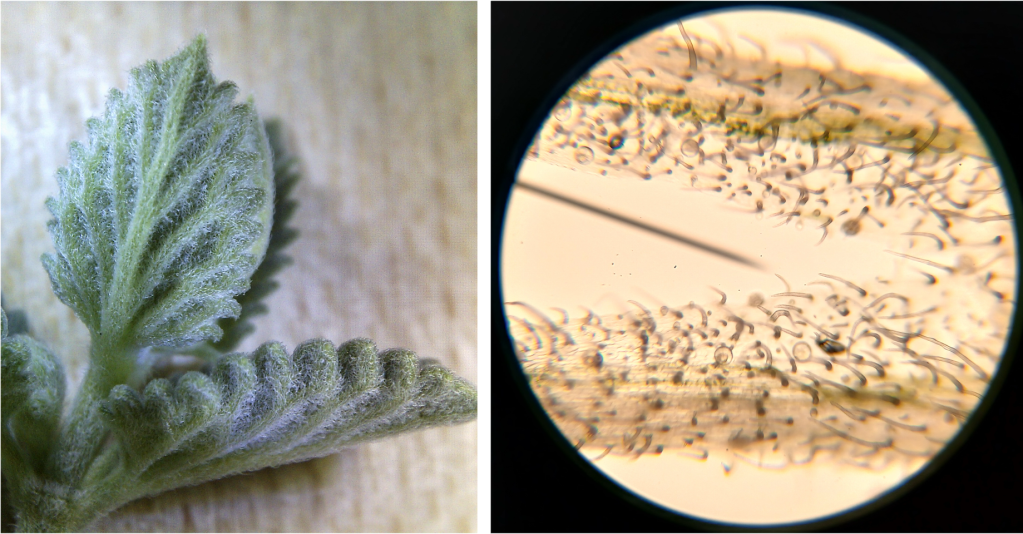

I also had a look at a random plant growing near the house. I don’t know what it is exactly, other than the fact that it is a member of the mint family. It is absolutely covered in tiny hairs, giving it a silvery appearance (Figure 7 left). I just had to look at those under the microscope (Figure 7 right). Wow, so many!

Figure 7. Trichomes on a “mystery mint”. Left: A whole leaf, showing its fuzzy appearance. Right: Epidermis under the microscope.

Gene of the week!

I am sorry for not talking more about the genetics underpinning trichome development. This lackluster performance is simply because I procrastinated and am running out of time I felt that a small blog post introducing the concept of trichomes wouldn’t do the topic justice.

Despite this, I am pleased to present our Gene of the Week! I couldn’t find an account of a tomato or sunflower mutant completely lacking trichomes… darn. However, the GLABRA1 (GL1) gene in Arabidopsis is required for trichome formation! The gene’s name comes from the word “glabrous,” which means “hairless.” Loss-of-function gl1 mutants in Arabidopsis lack trichomes [8]. The GL1 protein is a transcription factor, meaning that it interacts directly with DNA and affects the expression of other genes [8]. In this case, these other genes just happen to be required for differentiation of epidermal cells into trichomes. According to the UniProt databse, the GL1 gene is located at the AT3G27920 locus on Arabidopsis chromosome 3, and codes for a protein which is 228 amino acids long, with a mass of roughly 26 kDa.

Figure 8. Alphafold structure of AtGL1, taken from: https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/P27900. The 2-part DNA-binding domain can be seen in blue (which indicates a high degree of confidence in the predicted structure).

I did a quick search of the OMA database (https://omabrowser.org/oma/home/) to see if there are any known orthologs of GLABRA1 in tomatoes/sunflowers [1]. Orthologs are genes from different species which share a common ancestor. Identifying an ortholog of a gene with a known function in Arabidopsis in another plant species can allow us to guess that gene’s function (though of course only experiments can give us definitive information!). Surprisingly, the OMA database does not show any orthologs of GLABRA1 except in other members of the Brassicaceae family, of which Arabidopsis is a member. This raises the intriguing possibility that the transcriptional machinery which controls trichome development in the Brassicaceae may be different from those in other plant families.

Works cited:

[1] Altenhoff, A.M., Vesztrocy, A.W., Bernard, C., Train, C., Nicheperovich, A., Baños, S.P., Julca, I., Moi, D., Nevers, Y., Majidian, S., Dessimoz, C., & Glover, N.M. (2024). OMA orthology in 2024: improved prokaryote coverage, ancestral and extant GO enrichment, a revamped synteny viewer and more in the OMA Ecosystem. Nucleic Acids Research 52(D1), D513-D521. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkad1020

[2] Aschenbrenner, A., Horakh, S., & Spring, O. (2013). Linear glandular trichomes of Helianthus (Asteraceae): morphology, localization, metabolite activity and occurrence. AoB Plants 5, plt028. DOI: 10.1093/aobpla/plt028

[3] de Oliveira, J.R.F., de Resende, J.T.V., Maluf, W.R., Lucini, T., de Lima Filho, R.B., de Lima, I.P., & Nardi, C. (2018). Trichomes and Allelochemicals in Tomato Genotypes Have Antagonistic Effects Upon Behavior and Biology of Tetranychus urticae. Frontiers in Plant Science 9. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01132

[4] Galdon-Armero, J., Fullana-Pericas, M., Mulet, P.A., Conesa, M.A., Martin, C., & Galmes, J. (2018). The ratio of trichomes to stomata is associated with water use efficiency in Solanum lycopersicum (tomato). The Plant Journal 96(3), 607-619. DOI: 10.1111/tpj.14055

[5] Kasili, R., Huang, C., Walker, J.D., Simmons, L.A., Zhou, J., Faulk, C., Hülskamp, M., & Larkin, J.C. (2011). BRANCHLESS TRICHOMES links cell shape and cell cycle control in Arabidopsis trichomes. Development 138(11), 2379-2388. DOI: 10.1242/dev.058982

[6] Kaur, J., Kariyat, R. (2020). Role of Trichomes in Plant Stress Biology. In: Núñex-Farfán, J., Valverde, P. (eds) Evolutionary Ecology of Plant-Herbivore Interaction. Springer, Cham. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-46012-9_2

[7] Lou, T., Maria, N., Marie-Stéphane, T., & Navia, D. (2024). Tomato trichomes: trade-off between plant defenses against pests and benefits for biological control agents. Open Science in Acarology 64(4), 1232-1253. DOI: 10.24349/ej2w-b311

[8] Oppenheimer, D.G., Herman, P.L., Sivakumaran, S., Esch, J., & Marks, M.D. (1991). A myb gene required for leaf trichome differentiation in Arabidopsis is expressed in stipules. Cell 67(3), 483-493. DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90523-2

[9] Planelló, R., Llorente, L., Herrero, Ó., Novo, M., Blanco-Sánchez, L., Díaz-Pendón, J.A., Fernández-Muñoz, R., Ferrero, V., & de la Peña, E. (2022). Transcriptome analysis of aphis exposed to glandular trichomes in tomato reveals stress and starvation responses. Scientific Reports 12, 20154. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-24490-1

[10] Popowski, J., Warma, L., Cifuentes, A.A., Bleeker, P., & Jalaal, M. (2025). Glandular trichome rupture in tomato plants is an ultra-fast and sensitive defense mechanism against insects. Journal of Experimental Botany, eraf257. DOI: 10.1093/jxb/eraf257

[11] Kariyat, R.R., Smith, J.D., Stephenson, A.G., De Moraes, C.M., & Mescher, M.C. (2017). Non-glandular trichomes of Solanum carolinense deter feeding by Manduca sexta caterpillars and cause damage to the gut peritrophic matric. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 284(1849), 20162323. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2323

[12] Tissier, A. Trichome Specific Expression: Promoters and Their Applications. Editor: Yelda Özden Çiftçi. Transgenic Plants – Advances and Limitations. Publisher; 2012:353-378. Accessed August 8, 2025. DOI: 10.5772/32101

Leave a comment