What are plastids?

You’ve almost certainly heard about chloroplasts, which are the compartments inside plant cells that perform photosynthesis. They’re small, green, and plant cells have lots of them! Well, in tissues that lie above ground, anyway. Chloroplasts look like this:

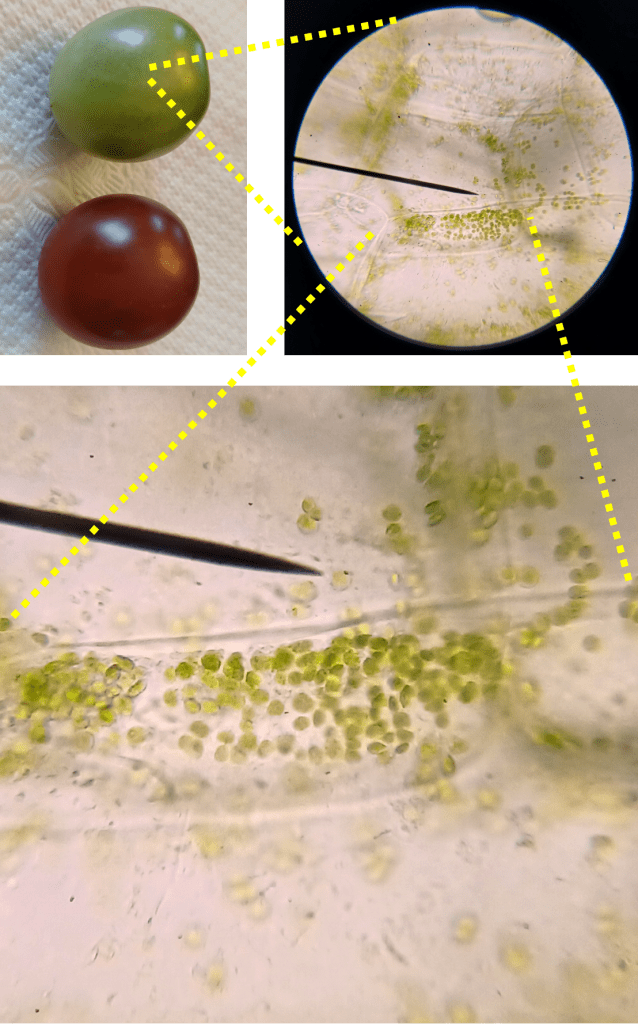

Figure 1: Chloroplasts inside tomato pericarp cells at 400X magnification (and further enlarged).

What if I told you that chloroplasts can transform? Chloroplasts are a kind of plastid, and plastids can take several different forms, depending on the cell type and the situation. In ripening fruits of the Solanaceae (including peppers and tomatoes), chloroplasts can become chromoplasts – structures which produce pigments that give the fruit color [8]. More on those in a bit.

What exactly are plastids? Plastids are specialized, membrane-bound organelles (subcellular structures) which carry out a variety of functions in plant cells. Plastids are notable because they have their own genome (DNA), which is separate from the main genome found in the nucleus of the plant cell [8]. This is because plastids are likely the result of endosymbiosis – they were once free-living organisms that were swallowed up by a larger cell, decided they liked it in there, and decided to set up shop [11]. Mitochondria are believed to have originated in a similar way. In fact, your mitochondria (along with the mitochondria of all plants) probably originated from the same endosymbiosis event [6]! It’s a shame humans didn’t get plastids, really. That would have been fun. Oh well…

Tomato chromoplasts:

Right, so I mentioned that tomato chloroplasts turn into chromoplasts during the ripening process. I just had to see this happening for myself! You too can do this at home if you have a basic light microscope that can take you to around 400X magnification. Seeing plastids with this equipment can be a little finicky. The trick is to take tissue samples that are as thin as possible – preferably only 1 cell thick. This is because plant tissue rapidly dims light from the microscope (due in part to the presence of plastids!) and scatters the light, making it hard to resolve a clear image. To take my pictures, I took the tiniest piece of pericarp (tissue under the epidermis) I could separate, and gently squished it between the slide and the coverslip to separate cells from each other. It was messy and annoying… but it worked in the end!

In the top left of Figure 2 below, you can see the tomatoes I sampled from. (In case you’re curious, the tomato variety used here is Black Opal, a kind of cherry tomato). The green tomato on the top is unripe, and the red tomato on the bottom is ripe and ready-to-eat! I began by looking for chloroplasts in the unripe tomato. You can see my whole field of view (Figure 2 top right), and a blown-up part of the same image (Figure 2 bottom). The chloroplasts are the little green blobby things. You can also see from this image that chloroplasts tend to accumulate near the edges of cells.

Figure 2. The image in the top left shows the tomatoes used for sampling. The top right shows pericarp cells from the unripe tomato at 400X magnification. The bottom image is a blown-up version of the same image, which clearly shows the chloroplasts.

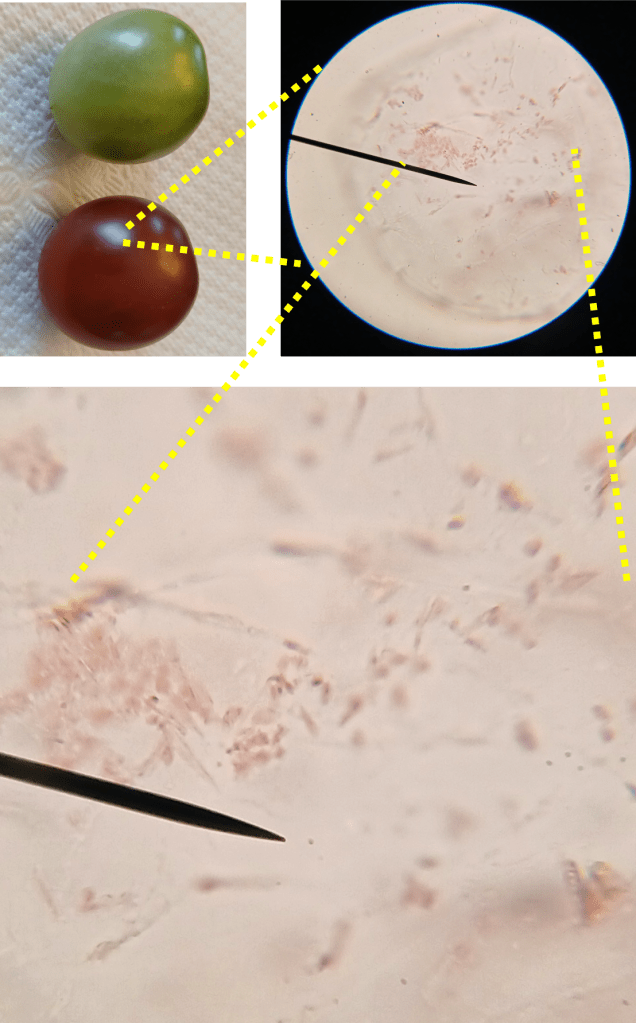

Okay, great! Now let’s look for the chromoplasts in the ripe tomato. Using the same sample preparation method, I was able to isolate a few pericarp cells from the ripe tomato and image them. If you look at Figure 3, the chromoplasts are the small red structures you can see inside the cell.

Figure 3. The image in the top left shows the tomatoes used for sampling. The top right shows pericarp cells from the ripe tomato at 400X magnification. The bottom image is a blown-up version of the same image, which clearly shows the chromoplasts.

Success! (I can’t believe that worked). To learn a bit more about tomato chromoplasts, let’s do a quick bit of Q and A.

1. Why are the chromoplasts red?

This color change occurs because chromoplasts accumulate various carotenoid pigments, including lycopene [12]!

2. Why are the chromoplasts all… spiky looking?

Great observation! This is because carotenoid pigments form long, crystal-like aggregates within the chromoplast [9]. Even though they may experience a dramatic increase in length, chromoplasts manage to maintain their membrane around the growing crystals [7].

3. Do chloroplasts experience changes in gene expression as they transform into chromoplasts?

Yes! One transcriptomic study showed that the expression of most plastid genes is downregulated as chloroplasts become chromoplasts, with the exception of a gene called accD [4]. The accD gene is involved in fatty acid synthesis and might be important for producing new membrane to encapsulate growing carotenoid crystals [4].

4. Do we know about other genes which are important for the chloroplast-chromoplast transition?

Yes! One interesting tomato mutant is the so-called “green flesh” mutant, which exhibits plastids that are apparently unable to complete the chloroplast-chromoplast transition [2]. The mutation which causes the green flesh phenotype was narrowed down to a gene called “STAY-GREEN” (SGR) in tomato [1]. Mutations in an ortholog of this gene in pepper cause a similar phenotype [1]. An ortholog has also been identified in the model plant Arabidopsis, though Arabidopsis does not possess chromoplasts [10]. Remember, orthologs are genes which share a common ancestor, but are found in separate species.

Now that we know a little bit more about tomato chromoplasts, I’d just like to wrap up this section with some bonus images. Figure 4 is an image of some cells I found which contain both chromoplasts AND chloroplasts. It is evidently mid-transition. Pretty neat!

Figure 4. Tomato pericarp cell containing both chloroplasts and chromoplasts.

Figure 5 is an image of tomato epidermal (skin) cells. As far as I can tell, these don’t really have any color at all. But man, look at those extra thick cell walls! If I had to make an uneducated guess, I’d say that these cell walls are the reason the skin is mechanically tougher than the squishy inside of the fruit.

Figure 5. Tomato epidermis at 400X magnification.

Pepper chromoplasts:

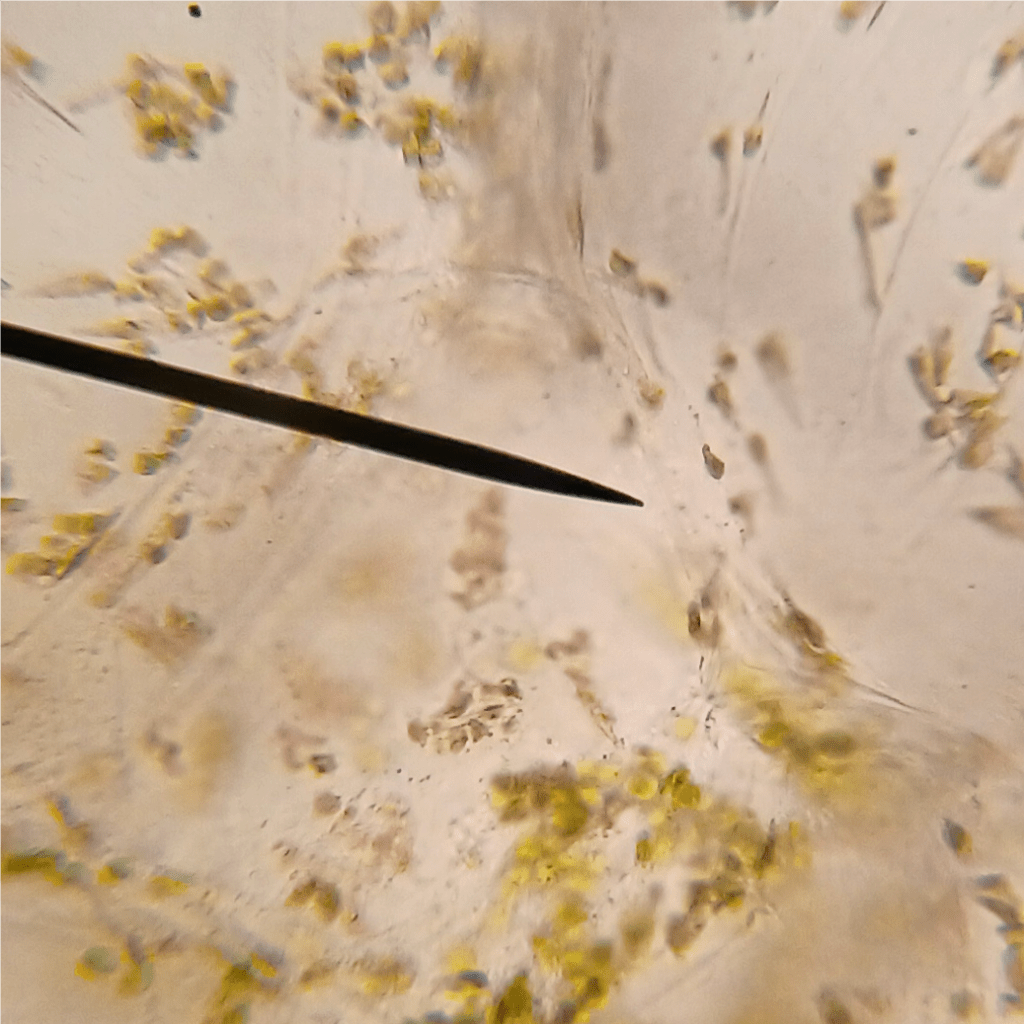

I’ve mentioned that peppers also possess chromoplasts in ripe fruit. I just so happen to have a couple pepper plants growing out on the deck, so I figured it wouldn’t hurt to have a look! Figure 6 shows my attempt to view chromoplasts in the pericarp cells of a Hot Red Cherry pepper. Not too shabby.

Figure 6. The image in the top left shows the peppers used for sampling. The top right shows pericarp cells from the ripe pepper at 400X magnification. The bottom image is a blown-up version of the same image, which clearly shows the chromoplasts.

Like tomato chromoplasts, pepper chromoplasts also contain high levels of carotenoid pigments, which give them their red color [5]. And just as in tomato, most plastid genes are downregulated during the chloroplast-chromoplast transition, except for accD [5]. Neat! You can see that the shape of these chromoplasts is a bit different, however. They’re more globular, without the crystal-like structures visible in tomato chromoplasts.

Gene of the week!

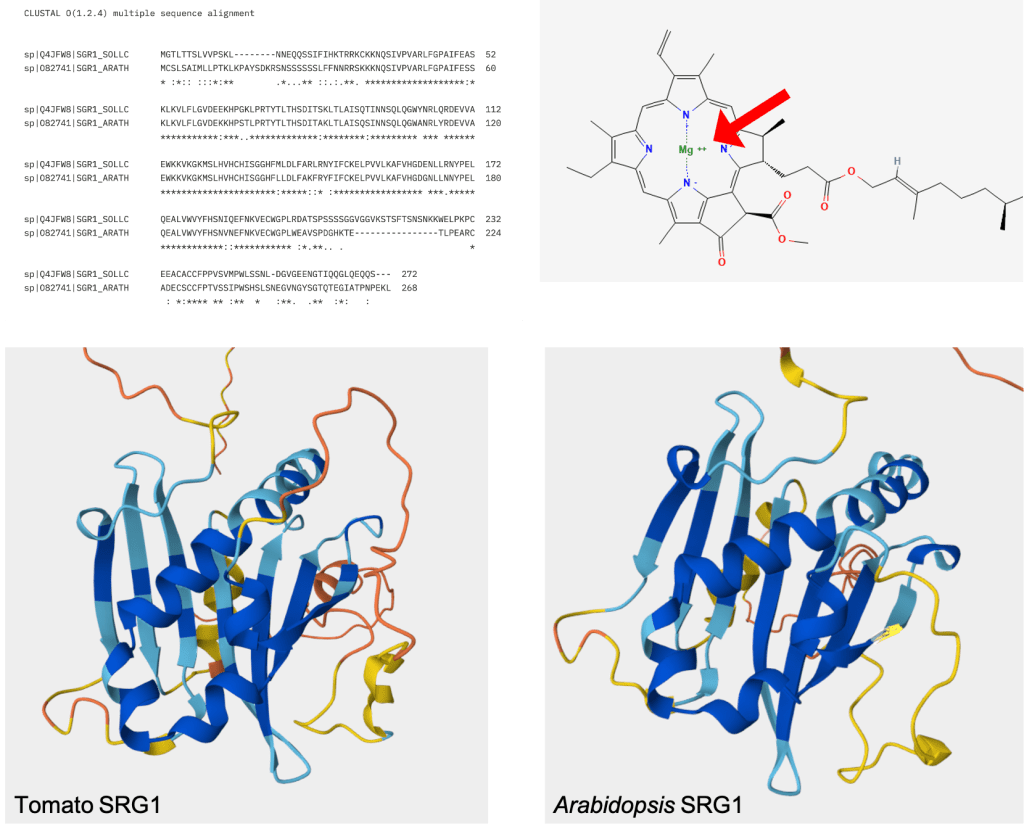

Well, that was fun! Er… I enjoyed myself anyway. All right then, here’s the gene of the week: SGR1 (STAY-GREEN 1)! I mentioned earlier that this gene is required to complete the chloroplast-chromoplast transition in tomatoes. How does it work?

I couldn’t find much info about the molecular function of SGR1 in tomatoes. However, an ortholog in Arabidopsis is known (See sequence alignment in Figure 7 top left)! In Arabidopsis, the SGR1 gene codes for a protein which functions as an enzyme called Magnesium Dechelatase [1]. This enzyme is important for the degradation of chlorophyll, as it removes the coordinated Magnesium atom from within the porphyrin ring of the molecule (Figure 7 top right). Chlorophyll degradation is of course important as chloroplasts transition to chromoplasts and lose their green coloration.

A predicted structure for the SGR1 protein is available for both tomato and Arabidopsis. They both look pretty similar, but this is unsurprising given the high sequence similarity between the two proteins. It is important to note that SRG1 in its native form might exist as an oligomeric complex – that is, multiple copies of the protein may interact and form a larger structure [3]. According to the UniProt database, the tomato protein is 272 amino acids long and has a mass of roughly 30 kDa.

Figure 7. Top Left: Aligned protein sequences of tomato and Arabidopsis SRG1. This alignment was made by inputting the UniProt protein sequences into Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo?stype=protein) with default settings. The two sequences have an extremely high level of similarity, even for orthologs. Top Right: Structure of chlorophyll a from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/12085802#section=2D-Structure), showing the location of the coordinated magnesium atom within the molecule. As chlorophyll is degraded, this magnesium atom is removed by SRG1. Bottom Left: Alphafold predicted structure of the tomato SRG1 protein, taken from its UniProt entry (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q4JFW8/entry#structure). Bottom Right: Alphafold predicted structure of the Arabidopsis SRG1 protein, taken from its UniProt entry (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/O82741/entry#structure).

Works cited:

[1] Barry, C.S., McQuinn, R.P., Chung, M., Besuden, A., & Giovannoni, J.J. (2008). Amino Acid Substitutions in Homologs of the STAY-GREEN Protein Are Responsible for the green-flesh and chlorophyll retainer Mutations of Tomato and Pepper. Plant Physiology 147(1), 179-187.

[2] Cheung, A.Y., McNellis, T., & Piekos, B. (1993). Maintenance of Chloroplast Components during Chromoplast Differentiation in the Tomato Mutant Green Flesh. Plant Physiology 101(4), 1223-1229.

[3] Dey, D., Dhar, D., Fortunato, H., Obata, D., Tanaka, A., Tanaka, R., Basu, S., & Ito, H. (2021). Insights into the structure and function of the rate-limiting enzyme of chlorophyll degradation through analysis of a bacteria Mg-dechelatase homolog. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 19, 5333-5347.

[4] Kahlau, S., & Bock, R. (2008). Plastid Transcriptomics and Translatomics of Tomato Fruit Development and Chloroplast-to-Chromoplast Differentiation: Chromoplast Gene Expression Largely Serves the Production of a Single Protein. The Plant Cell 20(4), 856-874.

[5] Rödiger, A., Agne, B., Dobritzsch, D., Helm, S., Müller, F., Pötzsch, N., & Baginsky, S. (2020). Chromoplast differentiation in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum) fruits. The Plant Journal 105(5), 1431-1442.

[6] Roger, A.J., Muñoz-Gómex, S.A., & Kamikawa, R. (2017). The Origin and Diversification of Mitochondria. Current Biology 27(21), PR1177-R1192.

[7] Rosso, S.W. (1968). The ultrastructure of chromoplast development in tomatoes. Journal of Ultrastructure Research 25(3-4), 307-322.

[8] Sadali, N.M., Sowden, R.G., Ling, Q., & Jarvis, R.P. (2019). Differentiation of chromoplasts and other plastids in plants. Plant Cell Reports 38(7), 803-818.

[9] Schweiggert, R.M., Mezger, D., Schimpf, f., Steingass, C.B., & Carle, R. (2012). Influence of chromoplast morphology on carotenoid bioaccessibility of carrot, mango, papaya, and tomato. Food Chemistry 135(4), 2736-2742.

[10] Shimoda, Y., Ito, H., & Tanaka, A. (2016). Arabidopsis STAY-GREEN, Mendel’s Green Cotyledon Gene, Encodes Magnesium-Dechelatase. The Plant Cell 28(9), 2147-2160.

[11] Zimorski, V., Ku, Chuan, Martin, W.F., & Guold, S.B. (2014). Endosymbiotic theory for organelle origins. Current Opinion in Microbiology 22, 38-48.

[12] Zita, W., Bressoud, S., Glauser, G., Kessler, F., & Shanmugabalaji, V. (2022). Chromoplast plastoglobules recruit the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway and contribute to carotenoid accumulation during tomato fruit maturation. PLOS One 17(12), e0277774.

Leave a comment