How do plants sense gravity?

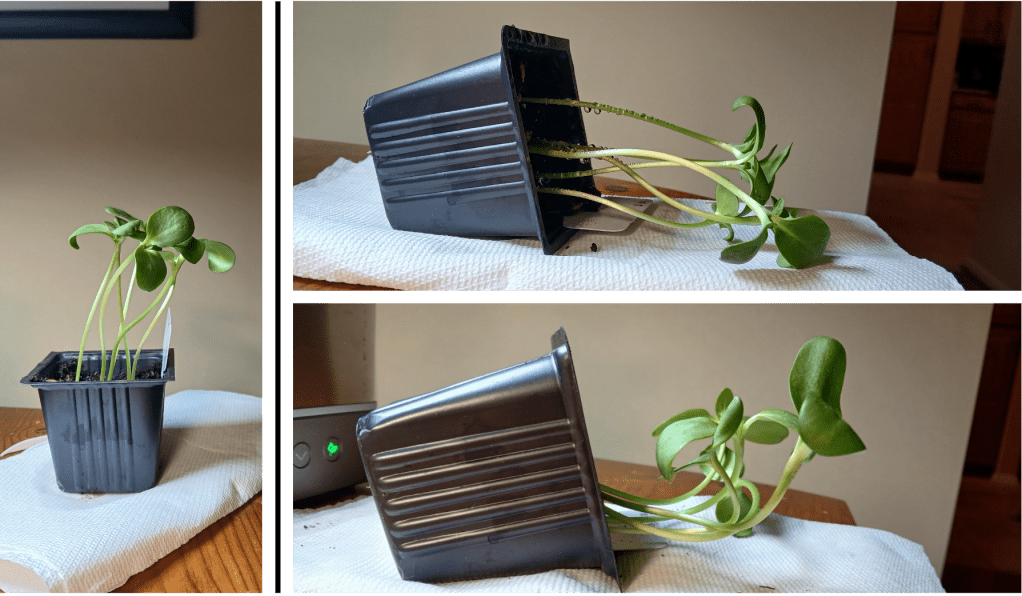

I’ve been growing some sunflower seedlings indoors under artificial lights. To demonstrate that plants can sense gravity, I turned one pot on its side and left it in a dark cupboard overnight. As you can see in Figure 1, the seedlings reorient their growth so that they once again face upward. But how do they know which way the gravity is going??

The answer is specialized plastids called amyloplasts, which contain large quantities of starch (“amlyo” is Greek for starch). We covered the concept of plastids in last week’s post. In short, plastids are organelles (subcellular structures) which have their own DNA and which live inside of plant cells. They can take on a number of different identities and may become chloroplasts, chromoplasts, amyloplasts, etc. Plants sense gravity using specialized amyloplasts called statoliths (Greek for “standing stone”, because they look like little stones! You’ll see why in a moment).

Figure 1. Left: sunflower seedlings used to test gravity-sensing. Right top: The same pot turned on its side. Right bottom: the same pot after sitting on its side in the dark overnight. One seedling was removed for microscopy (you’ll see why in a moment!)

Let’s see some statoliths!

Okey dokey! Let’s see some statoliths! But how?

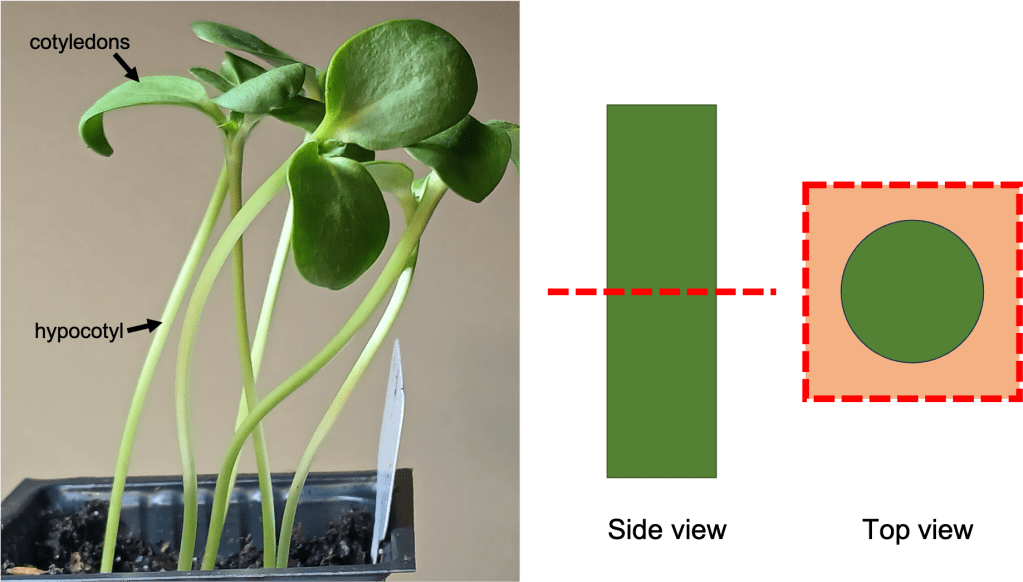

We’ll need to look at cells in the hypocotyl of our sunflower seedlings. The hypocotyl is the stem of the seedling (See Figure 2 left), which is derived from an embryonic structure that forms early in seedling development. Note that roots also have statoliths and can sense gravity independently of the stem… but I will discuss those in a later blog post.

Anyway, statoliths in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana are known to be found in the endodermal cell layer in stems [7]. Before going any further, I wanted to check whether the same was true for sunflower hypocotyls. To do this, I took a horizontal section through the hypocotyl (See Figure 2 right) and had a look under the microscope.

Figure 2. Left: Sunflower seedlings, showing the location of the hypocotyl and cotyledons (leaf-like structures).

The endodermis is a layer of cells that surrounds the pith and vascular tissue. In an unstained section of hypocotyl, it is extremely difficult to make out (See Figure 3 top left). Fortunately, we have some Lugol’s iodine at our disposal! You might remember from a science class at some point that iodine stains starch. Using Lugol’s iodine to stain our hypocotyl sections allows us to see the location of our statoliths – and by extension, the endodermis. You can see a hypocotyl section stained with Lugol’s iodine in the top right of Figure 3. A thin line of black spots belies the position of the endodermis. If you look even more closely, you can see individual statoliths within the endodermal cells (Figure 3 bottom).

Figure 3. Top left: Unstained section of sunflower hypocotyl at 100X magnification. Top right: Section of sunflower hypocotyl stained with Lugol’s iodine at 100X magnification. The position of the endodermis is indicated. Bottom: Endodermis and surrounding tissues at 400X magnification. Individual statoliths are visible.

Statoliths facilitate gravity sensing because they are denser than other cell contents and sink to the bottom of cells [7]. More on that in a minute. But this means that if we want to see statoliths in action, we need to take a vertical section of hypocotyl and view cells from the side. (See Figure 4 top for the location of the cuts I made). When we look at these vertical sections without staining, it is difficult to identify the endodermis cells (Figure 4 bottom left). However, after staining with Lugol’s iodine, the location of the statoliths/endodermis becomes clear (Figure 4 bottom right)!

Figure 4. Top: Locations of cuts to make to take vertical sections of hypocotyl tissue. Bottom left: Unstained hypocotyl section, with visible tissues labelled. Bottom right: Hypocotyl section stained with Lugol’s iodine. The endodermis, which contains statoliths, is visible.

Statolith sedimentation:

As previously mentioned, statoliths are believed to facilitate gravity sensing because they sink to the bottom of the cells. Sinking of the statoliths sets off a signaling cascade which ultimately results in a redistribution of the growth hormone auxin within the stem/hypocotyl, which leads to asymmetric cell elongation, which in turn allows plants to change the direction of their growth [5][6]. Exactly how the statolith sensing mechanism works is still being intensively studied. The review article by Kawamoto & Morita [4] provides an excellent summary of several lines of research, but we still don’t fully understand how we get from statoliths sinking –> auxin redistribution.

Er… right. Given that we don’t understand precisely how statolith-mediated gravity sensing works, how do we even know that these statoliths are important at all?? Fortunately, there is good evidence that points in this direction. For example, Arabidopsis mutants which lack the endodermal cell layer entirely are agravitropic (do not respond to gravity) [3]. Furthermore, Arabidopsis mutants which lack starch-filled amyloplasts, such as pgm (phosphoglucomutase) mutants, have a weaker gravitropic response (though it is not entirely gone) [2].

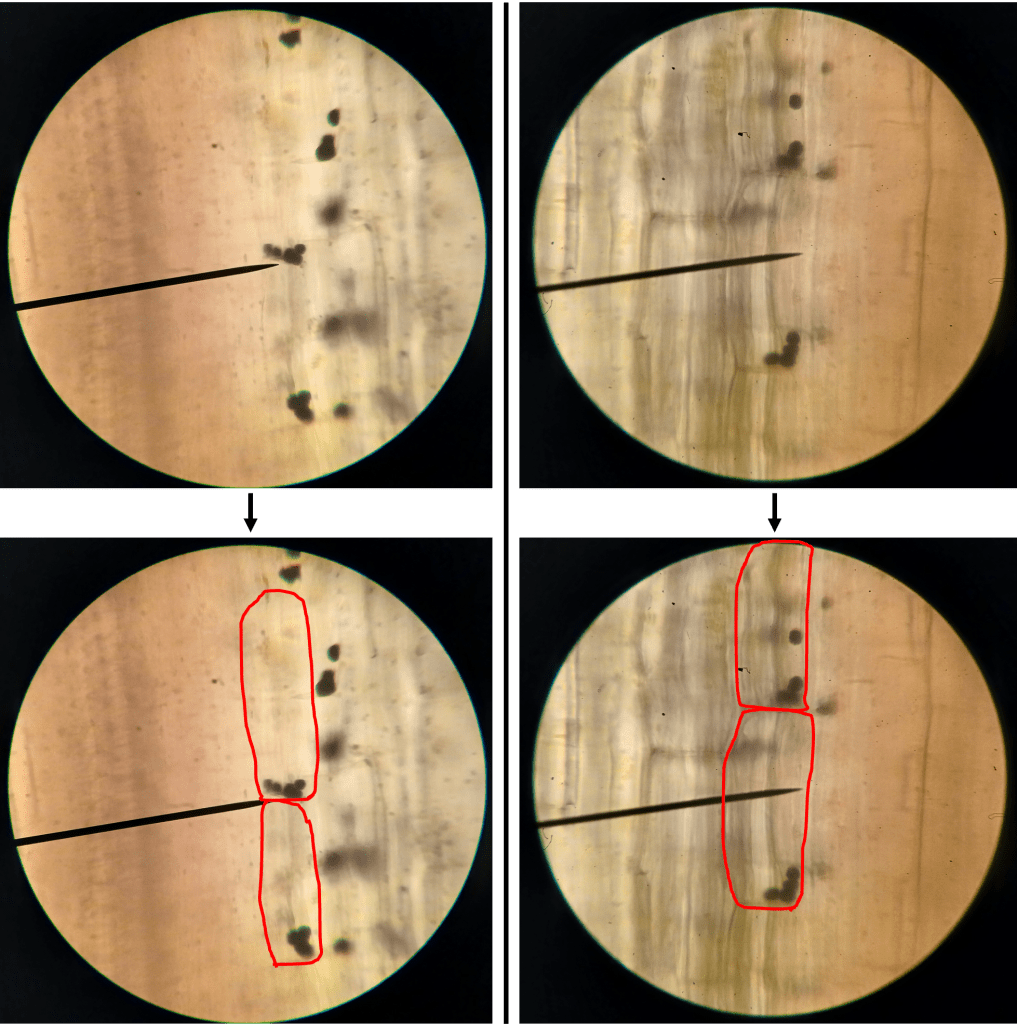

All very cool. But can we see statolith sedimentation for ourselves? Sure we can! First, I looked at statoliths in a vertical section of hypocotyl in a seedling that was growing vertically upwards. You can see that in Figure 5 that the statoliths accumulate on the bottom of the cells, as expected. Since the cell boundaries are difficult to see, I’ve highlighted them in red.

Figure 5. Statoliths in sunflower hypocotyls in a seedling which was growing vertically. Top: Unaltered images. Bottom: Images with cell boundaries highlighted for clarity.

Very good. Now, what happens if we tilt a seedling onto its side, wait a few hours, and then look at the statoliths? See for yourself in Figure 6! Here, statoliths accumulate on the lower side of the cells, as expected.

Figure 6. Statoliths in sunflower hypocotyls in a seedling which was tilted horizontally for several hours. Top: Unaltered images. Bottom: Images with cell boundaries highlighted for clarity.

Gene of the week:

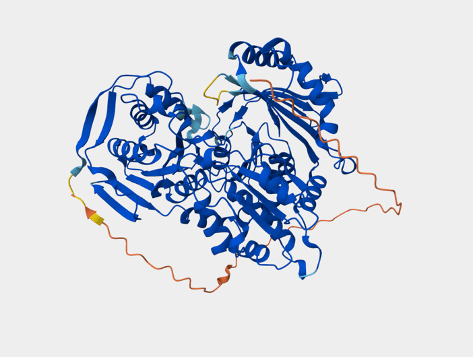

And just like that, it’s time for gene of the week! This week’s gene will be PGM (phosphoglucomutase) in Arabidopsis. PGM codes for an enzyme which is essential for the biosynthesis of starch in amyloplasts. As previously noted, pgm mutants have a reduced gravitropic response [2]. As expected, the UniProt database entry (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q9SCY0/entry#subcellular_location) notes that the PGM protein localizes to plastids. It also tells us that the PGM gene in Arabidopsis is located at the AT5G51820 locus on chromosome 5, and codes for a protein which is 623 amino acids long, with a mass of ~68 kDa. There is a nice alphafold structure available:

Figure 7. Alphafold structure of Arabidopsis PGM, taken from its UniProt entry.

I did a quick search of the OMA database (https://omabrowser.org/oma/home/) to see if there are any known orthologs of Arabidopsis PGM in sunflowers. For genes involved in such essential biochemical pathways, I would expect to see lots of orthologs with a high degree of sequence similarity across many species, so this should be a breeze. Indeed, OMA tells us that a predicted sunflower protein called “HELAN14524” exists, which has a similar sequence to Arabidopsis PGM. Furthermore, it is possible to predict that the sunflower PGM protein also localizes to plastids, because it contains a Transit Peptide sequence – a protein sequence motif that acts kind of like a “mailing address” to send proteins to plastids [1].

Works cited:

[1] Bruce, B.D. (2000). Chloroplast transit peptides: structure, function, and evolution. Trends in Cell Biology 10(10), 440-447.

[2] Caspar, T., & Pickard, B.G. (1989). Gravitropism in a starchless mutant of Arabidopsis. Planta 177, 185-197.

[3] Fukaki, H., Wysocka-Diller, J., Kato, T., Fujisawa, H., Benfey, P.N., & Tasaka, M. (2002). Genetic evidence that the endodermis is essential for shoot gravitropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 14(4), 425-430.

[4] Kawamoto, N., & Morita, M.T. (2022). Gravity sensing and responses in the coordination of the shoot gravitropic setpoint angle. New Phytologist 236, 1637-1654.

[5] Rakusová, H., Abbas, M., Han, H., Song, S., Robert, H.S., & Friml, J. (2016). Termination of Shoot Gravitropic Responses by Auxin Feedback on PIN3 Polarity. Current Biology 26(22), 3026-3032.

[6] Wang, X., Yu, R., Wang, J., Lin, Z., Han, X., Deng, Z., Fan, L., He, H., Deng, Z.W., & Chen, H. (2020). The Asymmetric Expression of SAUR genes Mediated by ARF7/19 Promotes the Gravitropism and Phototropism of Plant Hypocotyls. Cell Reports 31(2), 107529.

[7] Wyatt, S.E., Rashotte, A.M., Shipp, M.J., Robertson, D., & Muday, G.K. (2002). Mutations in the Gravity Persistence Signal Loci in Arabidopsis Disrupt the Perception and/or Signal Transduction of Gravitropic Stimuli. Plant Physiology 130(3), 1426-1435.

Leave a comment