I’ll be the first to admit that this title doesn’t make much sense. We’ll only be talking about one kind of plastid today: the etioplast! Etioplasts are plastids which inhabit plant tissues grown in the dark. They undergo rapid conversion to chloroplasts when light is available to power photosynthesis.

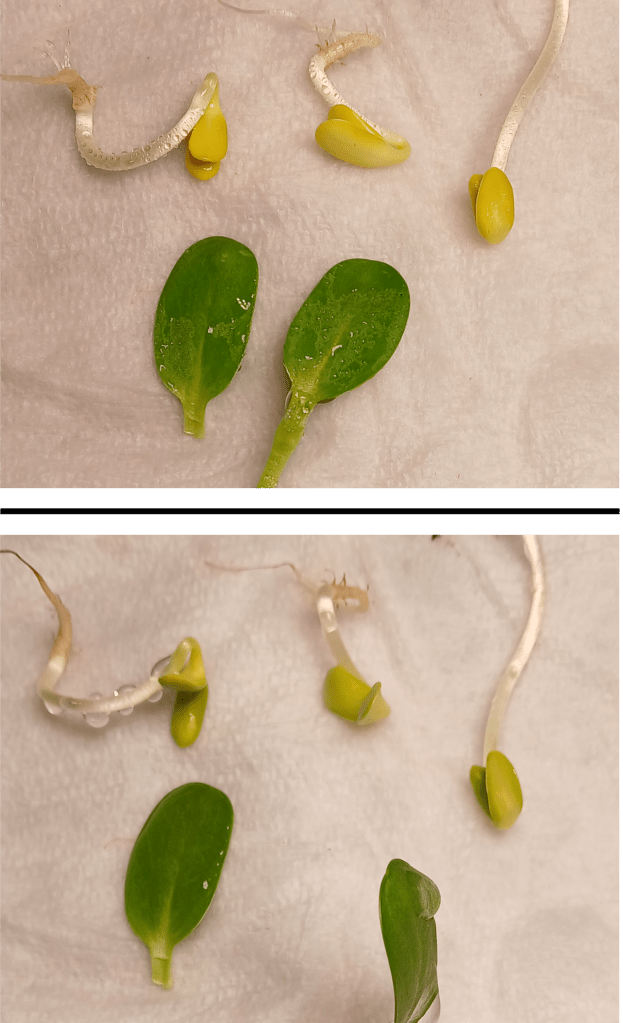

One of the easiest ways to “make” etioplasts at home is to grow seedlings in the dark. In Figure 1, you can see a sunflower seedling grown in the dark, side-by-side with seedlings grown in the light. These seedlings are all the same age, but there are some notable differences! For starters, the dark-grown seedling is a lot smaller. Furthermore, if we zoom in and look at the cotyledons (embryonic structures resembling leaves), we can see that they are yellow in the dark-grown seedling and green in the light-grown seedlings. This yellow coloration indicates the presence of etioplasts!

Figure 1. Left: Dark-grown sunflower seedling (in my hand) compared to light-grown sunflower seedlings of the same age. Right: A close-up of the cotyledons of the dark-grown seedling. They contain lots of etioplasts!

Ok, great! Can we see some etioplasts under the microscope?

… *sigh*. I tried. I really did. But I encountered some difficulties in doing so. The main problem is that the cotyledon cells in the dark-grown seedling are very small and densely packed together. Light attenuates quickly in such densely-packed tissue, making it difficult to visualize on the microscope (I just see dark-colored blobs). Fine. So next, I tried squishing the tissue in the hopes of splitting a few individual cells off to look at. But I found that the cells were very… crumbly. When I squished the tissue, the cells just ruptured and released their contents in a giant maelstrom of crap (See Figure 2 below). Some of the little globules you can see are probably etioplasts, but since they are not darkly pigmented, it is impossible to differentiate them from other cell contents.

Figure 2. The big mess made by squishing tissue from dark-grown cotyledons.

One possible explanation for the brittle-ness of the dark-grown cotyledon cells could be that their cell walls are thinner than in light-grown seedlings. I couldn’t find information about cotyledons specifically, but I did find this source which shows that cell wall thickness increases in the hypocotyls (stems)of sunflower seedlings after they are exposed to light [2]. This makes intuitive sense, since plants with access to light can photosynthesize and obtain more carbon to build cell walls with.

Wherefore art thou, chloroplast?

OK, so we can’t easily look at etioplasts directly. However, we can observe the etioplast-to-chloroplast transition by looking at whole seedlings! As I mentioned before, etioplasts become chloroplasts when they are exposed to light. We can see this change by looking at the color change of dark-grown cotyledons, from yellow to green! For an example, see Figure 3 below. This color change occurs because light stimulates production of chlorophyll, the green pigment required for photosynthesis.

Figure 3. Dark-grown seedlings vs. two dissected cotyledons from a light-grown seedling. Top: The dark-grown seedlings were just transferred to light. Bottom: The dark-grown seedlings were exposed to light for 8 hours.

How do etioplasts sense light, and how does this lead to chlorophyll production? I’m glad you asked! Etioplasts contain an important enzyme called protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (POR for short) [3]. This enzyme catalyzes a key step in chlorophyll biosynthesis. I was surprised to learn that the enzyme itself is light-activated – no other upstream signaling mechanisms are needed [3]! Very cool.

What would happen if a plant were deficient in the POR enzyme? As you might expect, Arabidopsis mutants with reduced levels of POR have reduced chlorophyll content and various other chloroplast defects [1]. Arabidopsis actually has 3 POR genes. Single mutants don’t have an obvious phenotype, but double mutants do [1]. The presence of multiple genes which can perform the same tasks is known as genetic redundancy. In the case of POR, the porB porC double mutant is seedling lethal – that is, plants cannot grow beyond the seedling stage before dying [1].

Mixed results:

We’re all scientists here. And scientists measure things! So…. Is there a way to quantify the greening process?

Well, sure. You could extract and quantify the concentration of chlorophyll in seedlings – but this requires a bunch of specialized equipment that I don’t have. However, I did come across this interesting paper which proposes a way to estimate chlorophyll content from RGB photographs, such as those you can take with a smartphone camera [4]! In particular, they found that the ratio of green to red pixel channel values was a reasonably good proxy for chlorophyll content [4]. This makes intuitive sense if you consider that in RGB, green color is created by having a high green channel value, while yellow is made by mixing red and green channels together. A low G:R ratio gives yellow and indicates low chlorophyll content, while a high G:R ratio gives green and indicates a high chlorophyll content!

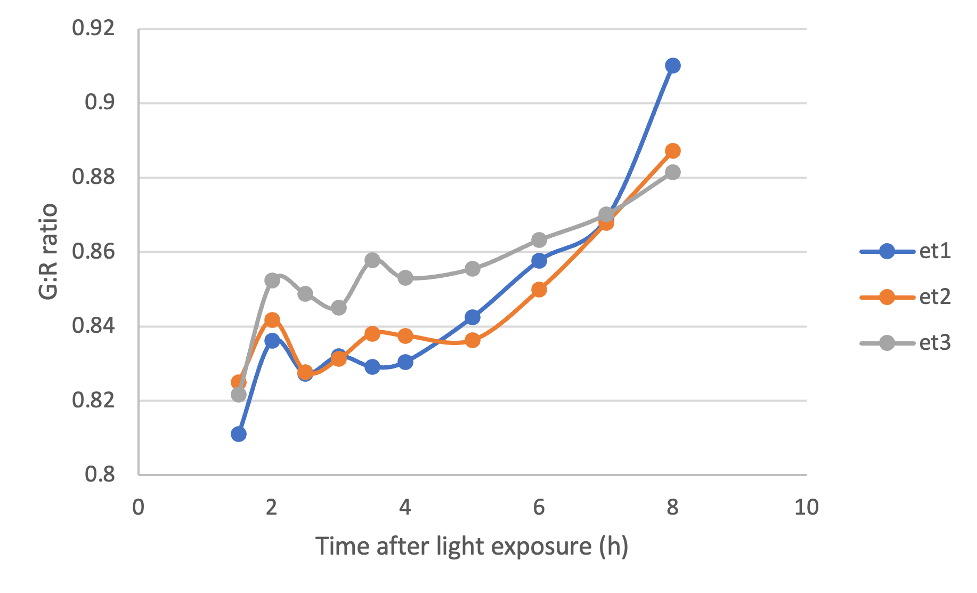

With this in mind, I photographed cotyledons from 3 different dark-grown seedlings after they were exposed to light, and quantified the G:R ratio of the pixels making up these cotyledons using an image-processing software called FIJI. Below, you can see that the G:R ratio for my three seedlings increases with time as they were exposed to light, indicating accumulation of chlorophyll. It works!

Figure 4. G:R ratio of rectangular selections of cotyledons from 3 dark-grown seedlings over time after they were exposed to light.

It… er… might have been a bit too early to celebrate. I also took the G:R ratio of a couple of light-grown cotyledons. We would expect these values to be relatively constant over time, since the chlorophyll content of mature cotyledons shouldn’t change meaningfully over only a few hours. However, if we plot the G:R ratio of light-grown cotyledons on the same graph as our dark-grown cotyledons, we get something that looks like Figure 5 below.

Figure 5. G:R ratio of rectangular selections of cotyledons from 3 dark-grown seedlings and 2 light-grown cotyledons over time.

What to heck?! The G:R ratios of the light-grown cotyledons are super variable! But why? Troubleshooting is an important part of the scientific process, so let’s think of some possibilities.

One issue that I found was that the surfaces of the light-grown cotyledons were somewhat reflective under my lights, especially when water droplets were present on their surface. Why were there water droplets? Since the cotyledons no longer had access to water, I was misting them with water constantly to keep them moist and alive. Unfortunately, this probably also had an effect on my photographs.

Another interesting thing that I noticed was that the blue channel values for pixels from the dark-grown cotyledons were virtually 0 throughout the entire experiment. However, the blue channel values for pixels from the light-grown cotyledons were higher and quite variable. In instances where the blue channel values were high, the green value channels tended to be lower, indicating a hidden relationship between the blue and green channels. It is possible that this “hidden relationship” made my results more variable. I don’t know exactly why this occurred. One interesting possibility is that this is due to the presence of other pigments (such as anthocyanins) in the light-grown seedlings, but I cannot say for certain.

I’m definitely going to try this again, with an improved protocol. Stay tuned.

Gene of the week:

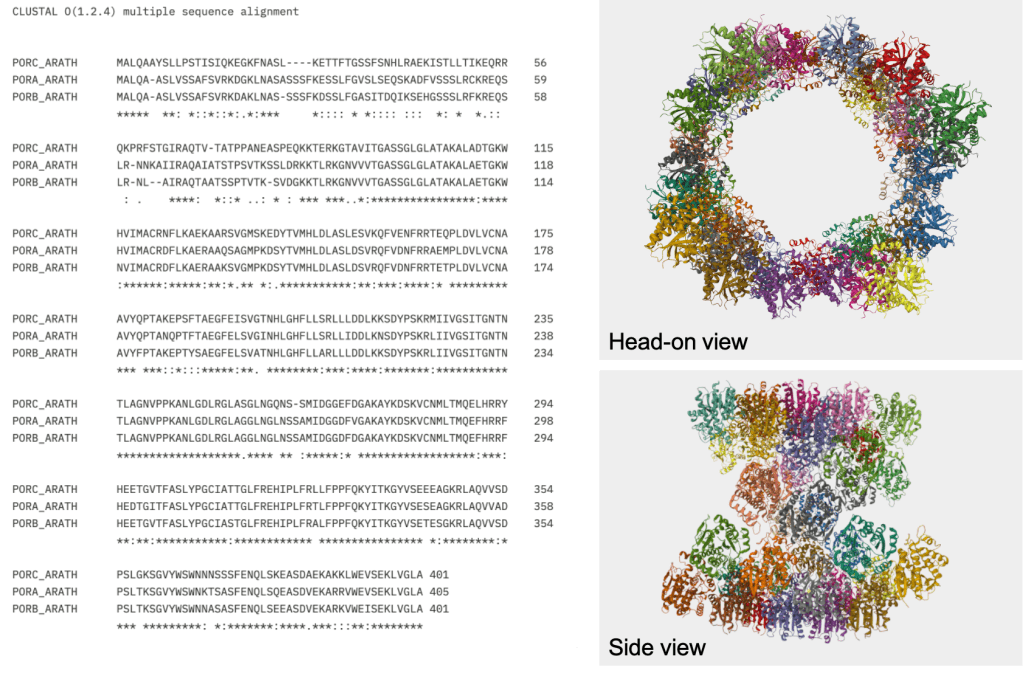

Well alrighty, it’s that time again! This week’s genes of the week will be the POR genes. As previously mentioned, Arabidopsis has 3 POR genes, which act redundantly with each other to catalyze chlorophyll production in etioplasts undergoing the transition to chloroplasts [1].

All of the POR proteins in Arabidopsis are roughly 400 amino acids long and have a mass of around 43 kDa (according to their respective UniProt entries). If we align their sequences using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo), we can see that their sequences are extremely similar (See Figure 6) – indicating that the 3 genes probably emerged from a recent duplication event.

But it gets crazier! I found this interesting paper which uses a technique called cryo-electron microscopy to look at the structure of POR [5]. They found that POR proteins come together to form enormous tubular structures! Apparently, these tubes help to organize internal membranes within the plastid [5]. And they look oh-so-cool! See Figure 6 below for an example of the structure.

Figure 6. Left: Sequence alignment of the 3 POR proteins from Arabidopsis. Right: Structure of PORB. The sequences and the structure were obtained from the following UniProt entries:

https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q42536/entry#sequences

https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P21218/entry#sequences

https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/O48741/entry#sequences

Works Cited:

[1] Frick, G., Su, Q., Apel, K., & Armstrong, G.A. (2003). An Arabidopsis porB porC double mutant lacking light-dependent NADPH:protochlorophyllide oxidoreductases B and C is highly chlorophyll-deficient and developmentally arrested. The Plant Journal 35(20, 141-153.

[2] Kutschera, U. (1990). Cell-wall synthesis and elongation in the hypocotyls of Helianthus annuus L. Planta 181, 316-323.

[3] Menon, B.R.K., Davidson, P.A., Hunter, C.N., Scrutton, N.S., & Heyes, D.J. (2009). Mutagenesis Alters the Catalytic Mechanism of the Light-driven Protochlorophyllide Oxidoreductase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285(3), 2113-2119.

[4] Nasoha, N.Z., Ibrahim, N.U.A., Harith, H.H., Jamaludin, D., & Abd Aziz, S. (2025). Linear regression and machine learning modelling for chlorophyll content estimation using leaf red, green, and blue images. Food Research 9(1), 94-100.

[5] Nguyen, H.C., Melo, A.A., Kruk, J., Frost, A., & Gabruk, M. (2021). Photocatalytic LPOR forms helical lattices that shape membranes for chlorophyll synthesis. Nature Plants 7, 437-444.

Leave a comment