Housekeeping!

I just wanted to apologize for missing last week’s regularly scheduled post. I have been travelling and did not have time to work on my blog. So… yeah, sorry about that. I’ll try to plan ahead better next time.

Before we start, I also wanted to let you know that I will be coming out with a new post every 2 weeks from now on, instead of every week. This is because I now have less free time than I did before (I got a job, lol). But don’t worry, we still have lots to talk about. Right then, to the post!

More about chamomile flowers than you ever needed/wanted to know:

I’ve been growing a chamomile plant in a little hydroponics unit sitting on a table indoors. It has been fun watching it grow, but recently I’ve become very interested in the flowers.

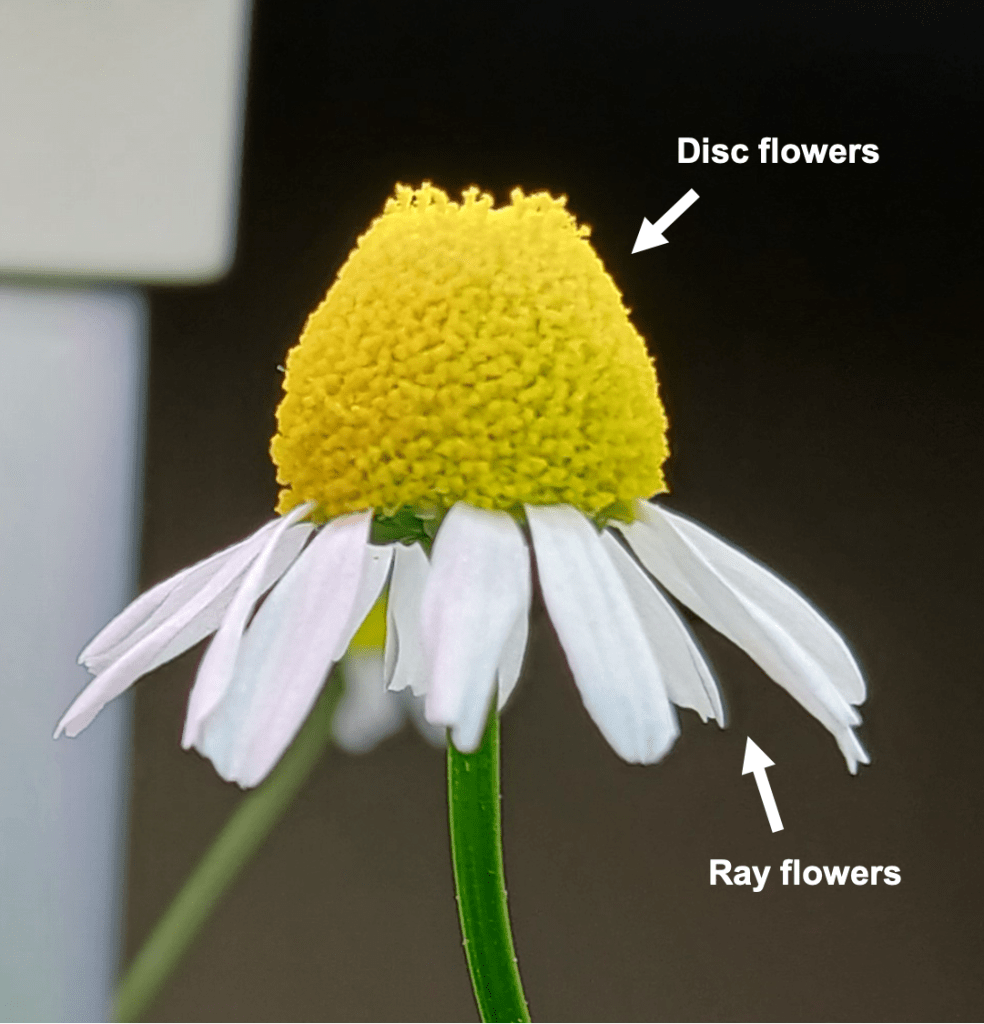

Like sunflowers, chamomile is a member of the Asteraceae. Members of this family have inflorescences – that is, clusters of many flowers – which together resemble a single flower. There are two kinds of flowers within the inflorescence: Ray flowers and disc flowers. In chamomile, ray flowers have large white petals and disc flowers have comparatively tiny petals. You can see an example of a chamomile inflorescence in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Chamomile inflorescence, showing the location of ray flowers and disc flowers.

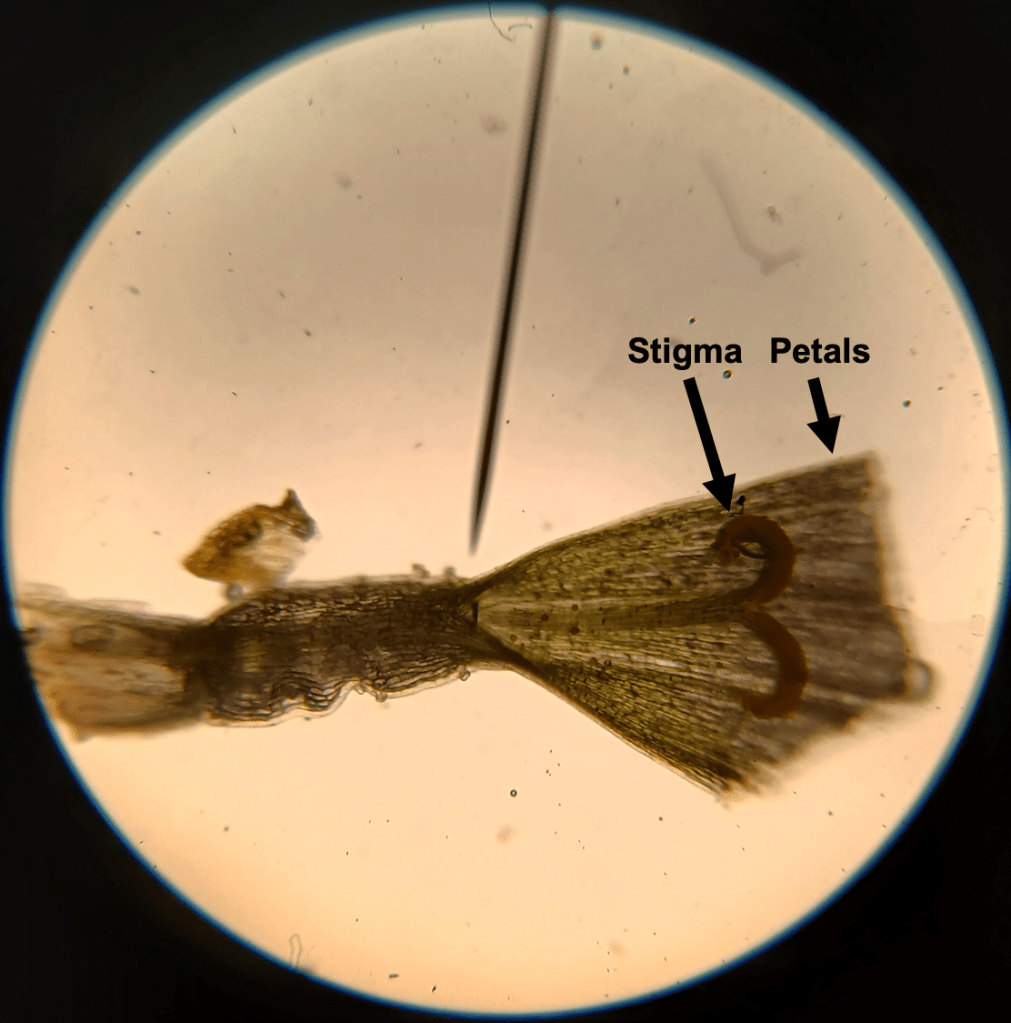

You might be looking at this picture and thinking: “I don’t see any flower-shaped things in there. It just looks like one big flower.” That’s fair. So, let’s take a look at the ray and disc flowers under the microscope! Figure 2 shows a side view of a disc flower. The flower is so tiny that you can see the individual cells which make it up. We can see the petals, the stigma (a female reproductive part), and even scattered pollen grains.

Figure 2. A chamomile disc flower at 100X magnification and blown up further to a larger size.

In Figure 3, we can see a ray flower. The structure of the female reproductive organs is similar to the disc flower; The stigma can be seen here, too. However, chamomile ray flowers are pistillate, meaning that they lack the male reproductive structures [6]. Neat! Furthermore, the petals are fused into a single large, flat plane that is comparatively enormous in size (I had to cut it off to fit the flower under the microscope).

Figure 3. A chamomile ray flower (with petals cut off) at 100X magnification. The fused petals are enormous and would have extended a long way to the right, had they not been severed.

Check this out!

This is all very fascinating, of course. But the REALLY cool thing about chamomile flowers is that they can move!

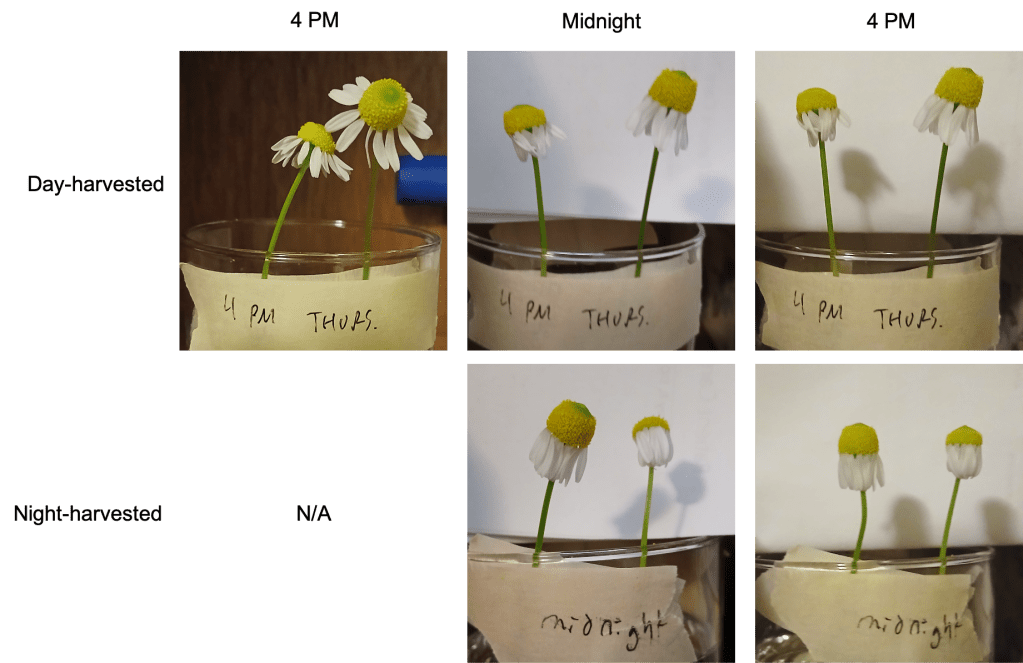

No, really! I’m not crazy…. They can move – just very slowly. Now, I’ve been growing my chamomile plant in day-night light cycles. During the day, the petals of the ray flowers are erect and point out sideways. At night, the petals of the ray flowers hang downwards. To illustrate this, I photographed the same 2 flowers over a couple days to show this movement in action – see Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Daily petal movements of chamomile ray flowers. This image series follows the same pair of flowers across 2 days.

While petal movements in chamomile are certainly striking, I should point out that daily rhythmic movements are actually quite common in plants. For example, if you’ve ever kept Oxalis triangularis (a common houseplant), you might also notice that the leaves and flowers move up and down, depending on the time of day (See Figure 5 below). Similarly, the leaves of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana also move up and down depending on the time of day [2], though this movement is somewhat less striking than in Oxalis and involves a different organ (the petioles as opposed to pulvini within leaves themselves).

Figure 5. Daily movements in an Oxalis kept as a houseplant. Left: The plant during the day. Right: The plant at night. These are my photos, but not my plant.

In Oxalis and Arabidopsis, these rhythmic movements are controlled by the circadian clock [2][3]. The circadian clock is an intrinsic biological rhythm which controls daily biological cycles. You have a circadian clock which controls your sleep patterns (this is why you sleep at roughly the same time each day) and various aspects of your metabolism. Plants also have a circadian clock which controls rhythmic movements, among other things.

Time to get a new watch…

One defining characteristic of circadian rhythmics is that they persist when organisms are moved from cycling to constant conditions [3]. For example, when Arabidopsis is shifted from day/night light cycles to constant light conditions, up-and-down leaf movements continue on a roughly 24-hour cycle [2]. With this in mind, I asked myself whether the flower movements in chamomile were also controlled by the circadian clock.

To test this, I severed some chamomile inflorescences, gave them some water, and put them into constant dark conditions (in my closet). I harvested two inflorescences at 4 PM (daytime), which roughly corresponds to the time when the ray flower petals are most erect. I also harvested two inflorescences at midnight. At this time, the ray flower petals hang loosely. (For your reference, my lights are kept on from 6 AM to 11 PM). Then, I tracked the movement of the flower petals over the next couple of days.

Hypothesis: If the flower movements are controlled by circadian rhythms, then the petals should continue to move up and down in constant dark conditions.

Great! We’re all set. So… what actually happened? The results actually did not support my hypothesis. As you can see in Figure 6, the inflorescences harvested during the day drooped after being moved to constant dark, and did not re-open. Meanwhile, the inflorescences harvested at midnight remained drooped throughout the entire experiment.

Figure 6. Petal movements in chamomile flowers kept in constant darkness. The top row of images shows flowers harvested at 4 PM, during the day. The bottom row of images shows flowers harvested at midnight. Images in each row are in chronological order from left to right.

Why did this happen? I don’t know, but I’ve thought of a couple possible explanations. Let’s discuss.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATION 1: Flower movements in chamomile are not controlled by the circadian rhythm, but are rather directly controlled by present light levels.

I think this is unlikely for a couple of reasons. First, I observed that the petals on my chamomile plant tend to start drooping at the end of the day, BEFORE the lights go off. In other words, they are anticipating an impending change in light conditions. This would not happen if petal movements were determined by light alone.

I also tested this theory directly. To do this, I took my chamomile inflorescences that had been sitting in the dark for a few days (and were super droopy) and moved them back into the light. If light is necessary and sufficient to cause petals to stand up, then I would expect the petals in my cut inflorescences to do just that. They appeared to make what seemed to be a half-hearted attempt to stand up after many hours of light exposure, but ultimately did not move much. Interesting.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATION 2: The act of severing inflorescences from the rest of the chamomile plant results in a loss of circadian petal movement. I can think of two possible reasons for this. One possibility is that petal movements are controlled remotely by a circadian oscillator in another part of the plant (the leaves, for instance). Another possibility is that petal movement requires a specific nutrient, which severed flowers in water would be unable to acquire.

Sadly, I still haven’t had the time to test these ideas. This is because I cut off all of my chamomile flowers for my previous experiment (and I didn’t have many to begin with!). However, when my plant recovers and generates more flowers, I should be able to do a small experiment. If rhythmic petal movements require that the inflorescence be attached to the rest of the plant, then these movements should persist if the whole plant is transferred to constant dark conditions. I’ll let you know when the results of that test become available.

Gene of the week:

Tragically, I was not able to find any research about the genetics underpinning flower petal movements in chamomile or in a closely related species. Therefore, I have been forced to choose a Gene of the Week which is only tangentially related to what we were talking about. I still think you’re going to like it, though.

This week’s Gene of the Week is ELF3. Funny name, eh? ELF3 stands for “EARLY FLOWERING 3”, because Arabidopsis plants lacking a functional copy of this gene flower early [4]. … I guess that makes sense. The ELF3 protein is an important component of the circadian clock in Arabidopsis. Without it, plant movements and other circadian-regulated processes are arrhythmic in constant light [5]. Interestingly however, elf3 mutant Arabidopsis plants still maintain rhythmicity in constant dark conditions [5].

What does the ELF3 protein do? Famously, it is part of a larger protein complex (called the Evening Complex) which controls the expression of other genes [8]. As its name suggests, the Evening Complex is most active in the evening. Very generally, the Evening Complex helps to ensure that daily oscillations in gene expression occur at the correct time. Interestingly, recent research has also shown that ELF3 also has functions independently of the evening complex [7]… so it does rather a lot!

Now, the BIG question: Does chamomile have an ELF3 gene? Well, my favorite ortholog database (OMA: https://omabrowser.org/oma/home/) does not include chamomile. And I wasn’t able to find a proteome for chamomile, either. And a Blast search (think search engine, but for DNA/protein sequences) using the Arabidopsis ELF3 DNA sequence as a query did not find an ELF3 DNA sequence in chamomile. What to do?

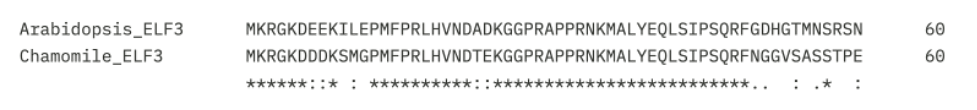

Fortunately, there is a reference genome for chamomile which is partially annotated [1]! The authors of this paper identified a probable ELF3 ortholog, which is noted in their supplemental data. If we take the first exon in this gene and translate it into a predicted protein sequence (beginning with the predicted start codon), and compare it to the Arabidopsis ELF3 protein sequence, we find that the two are very similar! (Figure 7). So it seems chamomile has an ELF3 ortholog after all.

Figure 7: Alignment of the beginning of the Arabidopsis and chamomile ELF3 proteins (chamomile is a hypothetical protein sequence).

Works cited:

[1] Cho, W., Feng, J., Knauft, M., Albrecht, S., Himmelbach, A., Otto, L., & Mescher, M. (2025). An annotated haplotype-resolved genome sequence assembly of diploid German chamomile, Matricaria chamomilla. Scientific Data 12, 358.

[2] Dornbusch, T., Michaud, O., Xenarios, I., & Fankhauser, C. (2014). Differentially Phased Leaf Growth and Movements in Arabidopsis Depend on Coordinated Circadian and Light Regulation. The Plant Cell 26(10), 3911-3921.

[3] Edery, I. (2000) Circadian rhythms in a nutshell. Physiological Genomics 3, 59-74.

[4] Hicks, K.A., Albertson, T.M., & Wagner, D.R. (2001). EARLY FLOWERING 3 Encodes a Novel Protein that Regulates Circadian Clock Function and Flowering in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 13(6), 1281-1292.

[5] Hicks, K.A., Millar, A.J., Carré, I.A., Somers, D.E., Straume, M., Meeks-Wagner, D.R., & Kay, S.A. (1996). Conditional circadian dysfunction of the Arabidopsis early flowering 3 mutant. Science 274(5288), 790-792.

[6] Matricaria chamomilla (Wild chamomile, German chamomile).Retrieved September 16, 2025, from: https://wwv.inhs.illinois.edu/data/plantdb/detail/2185

[7] Nieto, C., López-Salmerón, V., Davière, J., & Prat, S. (2015). ELF3-PIF4 interaction regulates plant growth independently of the Evening Complex. Current Biology 25(20, 187-193.

[8] Nusinow, D.A., Helfer, A., Hamilton, E.E., King, J.J., Imaizumi, T., Schultz, T.F., Farré, E.M., & Kay, S.A. (2011). The ELF4-ELF3-LUX complex links the circadian clock to diurnal control of hypocotyl growth. Nature 475(7356), 398-402.

[9] You, L., Tuo, W., Dai, Z., Wang, H., Ahmad, S., Peng, D., & Wu, Shasha. (2023). Effects of light intensity, temperature, and circadian clock on the nyctinastic movement of Oxalis triangularis ‘Purpurea’. Technology in Horticulture 3, 11.

Leave a comment