Just a quick one this week!

I noticed these magnificent Jewelweeds (Impatiens capensis) while traveling a few weeks ago, and I just wanted to share them with you. They’re absolutely everywhere, and they have lovely flowers! They’re native to North America, and can generally be found in low-lying areas with wet soil.

Figure 1. Left: Patch of spotted jewelweed. Right: Close-up of the flowers.

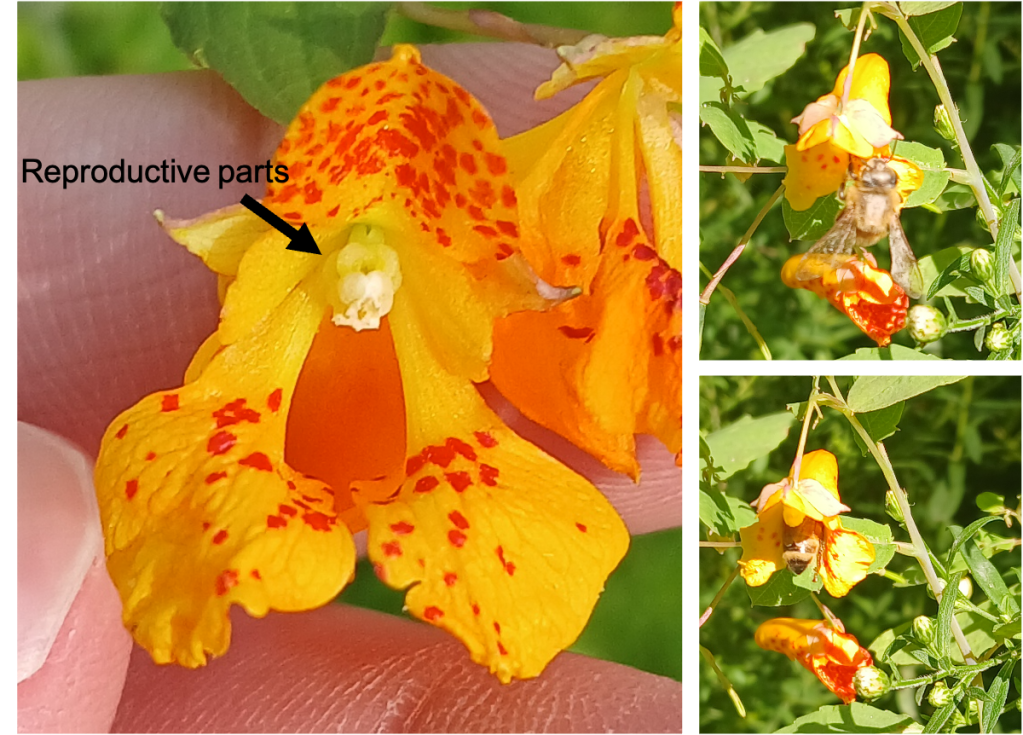

The bees really seem to like them! However, getting to the nectar seems to be a bit of work; The bees have to dive deep into the flower to find it. As they do so, they brush up against the reproductive parts of the flower, ensuring pollination.

Figure 2. Left: Closeup of an Impatiens flower showing the location of the reproductive organs. Right: A bee inspecting and entering a flower to find nectar.

Fun! But what happens after the plant is done flowering is far more interesting. Jewelweeds are also known by another name – “touch-me-nots”. This is because the mature fruits explode at even the slightest touch! Actually, while I was working on this, I noted that this behavior is very similar to that of the Himalayan Balsam, which I have previously encountered while travelling. If you live in Europe or Asia, you may have seen them around. They have lovely purple flowers and explosive fruits. Anyhoo, I later found out that touch-me-nots and himalayan balsam are very closely related to each other, and are even in the same genus… so that makes sense. I feel pretty silly now, really. The explosive seed dispersal process has actually been studied in both species [1][3]. I’ll admit, both of these papers go way over my head – but it’s comforting to know that someone else has worked on this!

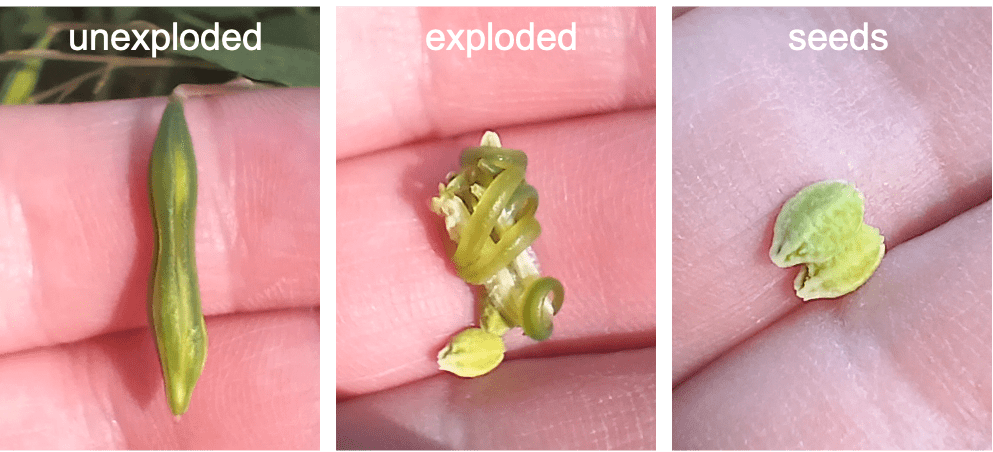

Right, it’s time for a demonstration. In Figure 3 below, I show an unexploded seed pod on the left, an exploded seed pod in the middle, and the seeds on the right.

Figure 3. Left/middle: Views of an Impatiens seed pod before and after the explosion. Right: Seeds!

As you can see, the walls of the fruit coil tightly during the explosion. This indicates that they are under a great deal of tension in the unexploded fruit. Deegan (2012) show that the fruit walls are held under tension by a membrane which connects them together [1]. The slightest tear in this membrane triggers a catastrophic failure in the structure [1].

How fast does this happen in our jewelweeds? Hayashi et al. (2009) report that the explosion takes approximately 4 milliseconds. I tried to film a seed pod using my phone, which can film at 120 fps. I got the following 4 consecutive frames:

Figure 4. Seed ejection sequence. These are consecutive frames from a 120 fps video. An ejected seed (marked with a red arrow) can be seen travelling away from the seed pod.

As you can see from Figure 4, the ejection begins in the second frame and is already complete by the third frame. The time between frames is ~8.33 ms, so our estimate roughly agrees with the measurement from Hayashi et al.

Alas, I have not been able to find much information about the genetics of explosive seed dispersal. So, I will leave you with this: A genome for Impatiens capensis has been published [2]! I’m sure some folks are going to have plenty of fun with this in the future.

Works cited:

[1] Deegan, R.D. (2012). Finessing the fracture energy barrier in ballistic seed dispersal. PNAS 109(14), 5166-5169.

[2] Gadagkar, S.R., Baeza, J.A., Buss, K., & Johnson, N. (2023). De-novo whole genome assembly assembly of the orange jewelweed, Impatiens capensis Meerb. (Balsaminaceae) using nanopore long-read sequencing. PeerJ 11, e16328.

[3] Hayashi, M., Feilich, K.L., & Ellerby, D.J. (2009). The mechanics of explosive seed dispersal in orange jewelweed (Impatiens capensis). Journal of Experimental Botany 60(7), 2045-2053.

Leave a comment